Tara Trinley and I were having a conversation about my work as a goldsmith and she looked at me with her beautiful, sky-like eyes and said: ‘Write about the way you work! Share your story!’ This invitation awoke a new way of looking into the work I do, and the short writing I present to you now is an expression of this. I have chosen to tell the following story as an introduction, because it holds the values of the way I try to work and I also want to pay homage to all the precious-metal masters, who have passed on their knowledge from generation to generation.

In 2002 I travelled from Denmark to India in a group guided by Lakha Rinpoche. As always, Rinpoche and his wife had prepared every detail carefully, and therefore I knew that we would be visiting Norbulinka Institute near Dharamsala. At the Institute they have a workshop for the art of statue-making. As I am a goldsmith, I thought it would be appropriate to bring a small gift in form of some tools to the workshop. So I packed some files and polishing tools in my suitcase, hoping it would find its safe way through security check. I also brought a picture from within my own workshop showing me with tools and works, to visually explain that I am a goldsmith. It is not tradition for women to perform that kind of work in Tibet, and therefore I thought that a picture would help me to connect on a professional level.

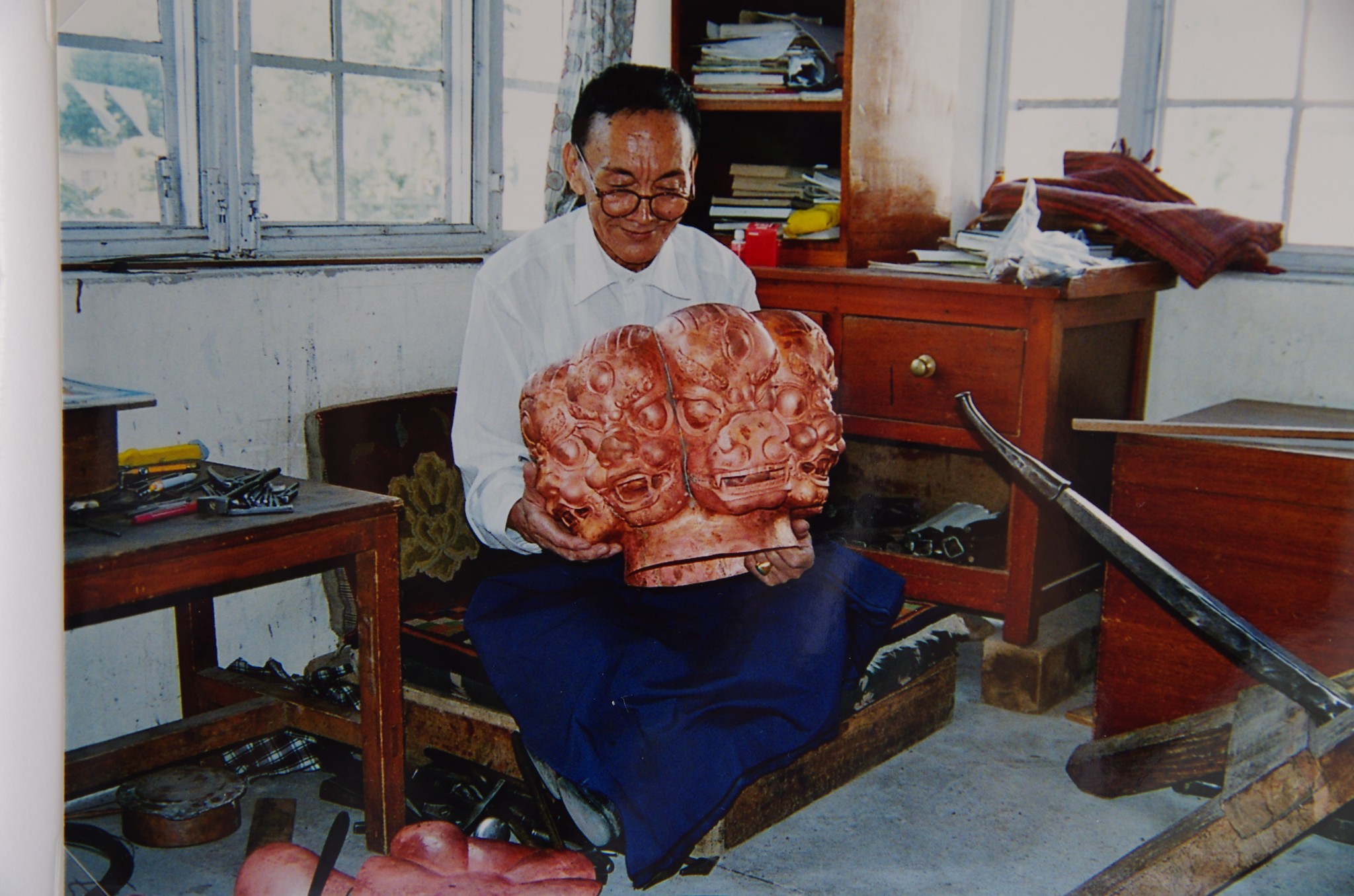

When the day arrived I was so excited to finally see this place where the old tradition of statue making was kept alive. The group walked into the workshop and Rinpoche officially greeted the old statue-making master, Pemba Dorje, who was both master and teacher of the workshop. I looked around. The students were sitting on the floor, working with worn out tools and making beautiful handcrafts with very limited resources. Seeing this made me realize, that my symbolic gift was actually needed, and a wish to raise funds for this workshop arose in me.

I had been so absorbed in thinking about how to raise funds and I was also trying to get an overview of what was needed in the workshop, I didn’t notice Rinpoche and the group had left and continued to the next building. Suddenly in a hurry, I asked one of the young students to translate for me, so I could give the tools I had brought to the master. I felt really small and professionally humbled being in the presence of this great statue master. He was so modest and kind, and we talked as best as we could, with the student as our bridge to understanding. I showed him the photo of my workplace and he looked very interested and familiar at all the tools in the picture. Then, for some unknown reason, he turned the plastic folder and went completely still. He sat quietly looking at the picture with tears coming to his eyes.

He placed the picture on his head and put it on his table, keeping it as a precious gift. In this moment I was completely humbled. Whenever I travel, I carry a picture of Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche with me. This picture was the very picture that brought tears to master Pemba Dorjes eyes. His devotion was what humbled me. Then, as if a lightning had hit him, he got up, went to his desk and opened all the drawers. He rapidly selected a couple of pictures of his work and gave them to me. I thanked him, quite overwhelmed, and went out of the building to catch up with the group. Then I heard a voice calling from behind: ‘Madame, please wait! ’ and the student came running down the stairs. ‘Master Dorje would like you to have some more pictures’.

And the 72 year old Pemba Dorje came walking down to me with a lot more pictures. I feel, that what I was really given, beside from the pictures, was an attitude to learn from. An attitude of loving kindness, generosity and whole-hearted dedication. I found Rinpoche and the group in another building and the journey went on. Some weeks later I was home again trying to write a letter that could raise funds, and then the good news came: benefactors from US had sponsored an upgrade of the workshop at Norbulinka. Many eyes, many hearts can make positive changes. Statue Master Pemba Dorje passed away in 2011 and his work continues in a seamless way.

And now to me…

I was born at home where my father also had his goldsmith workshop. My cot was placed in front of my father’s workbench, and so I was influenced by the sounds, smells and sights of this particularly handcraft from the very beginning of my life. Tragically my mother died when I was little, and our father became a single parent to me and my 3 year older brother.

We moved into a house in a town closer to grandparents, and our father settled his workshop on the ground floor. Now I had a daily rhythm in and out of the workshop, coming home from school, run errands, helping with smaller tasks in the workshop. Soon my father found out that I had a flair for the handcraft and he took me to exhibitions and trade shows, taught me history of jewel art and always answered all my questions like ‘What is the name of this gemstone? Where does it come from? How did the Vikings make there jewelry? How do I draw a ring?’

We moved into a house in a town closer to grandparents, and our father settled his workshop on the ground floor. Now I had a daily rhythm in and out of the workshop, coming home from school, run errands, helping with smaller tasks in the workshop. Soon my father found out that I had a flair for the handcraft and he took me to exhibitions and trade shows, taught me history of jewel art and always answered all my questions like ‘What is the name of this gemstone? Where does it come from? How did the Vikings make there jewelry? How do I draw a ring?’

He was not just my father, he was also my teacher. Although he was working day and night to provide for two children, his enthusiasm for the handcraft never faded. It had a catching effect on both my brother and me, and both of us ended up becoming goldsmiths. During my career I have found, that what keeps it alive, fresh and enjoyable for me is the process of working with unique pieces in close cooperation with the customer.

It’s a process that involves mostly listening and asking the right questions. This always requires time and intimate conversations. We talk about their deepest values in life. What is most important for them. How it has manifested in their life. What symbolizes these values most precisely etc. and I start the process of putting it in to form. First I draw sketches and then we talk back and forth while the pen moves on the paper. It’s a really enjoyable process and it’s a privilege to meet people this way. During this process a time comes when we both know: ‘there it is!’

What wasn’t seen before, is suddenly obvious. After that, the rest is up to me. Melting gold or silver, hammering, soldering, polishing, setting stones and so on. This is the period of solitude. It demands skills and precision as one-pointed, effortlessly concentration. My workshop is designed in such a way, that I can easily move between the workbench and the meditation cushion. This helps me balance the inside and outside activity while working. I find that whether I’m alone or with others, it’s the intimate connection between true being and doing that brings fullness to life.