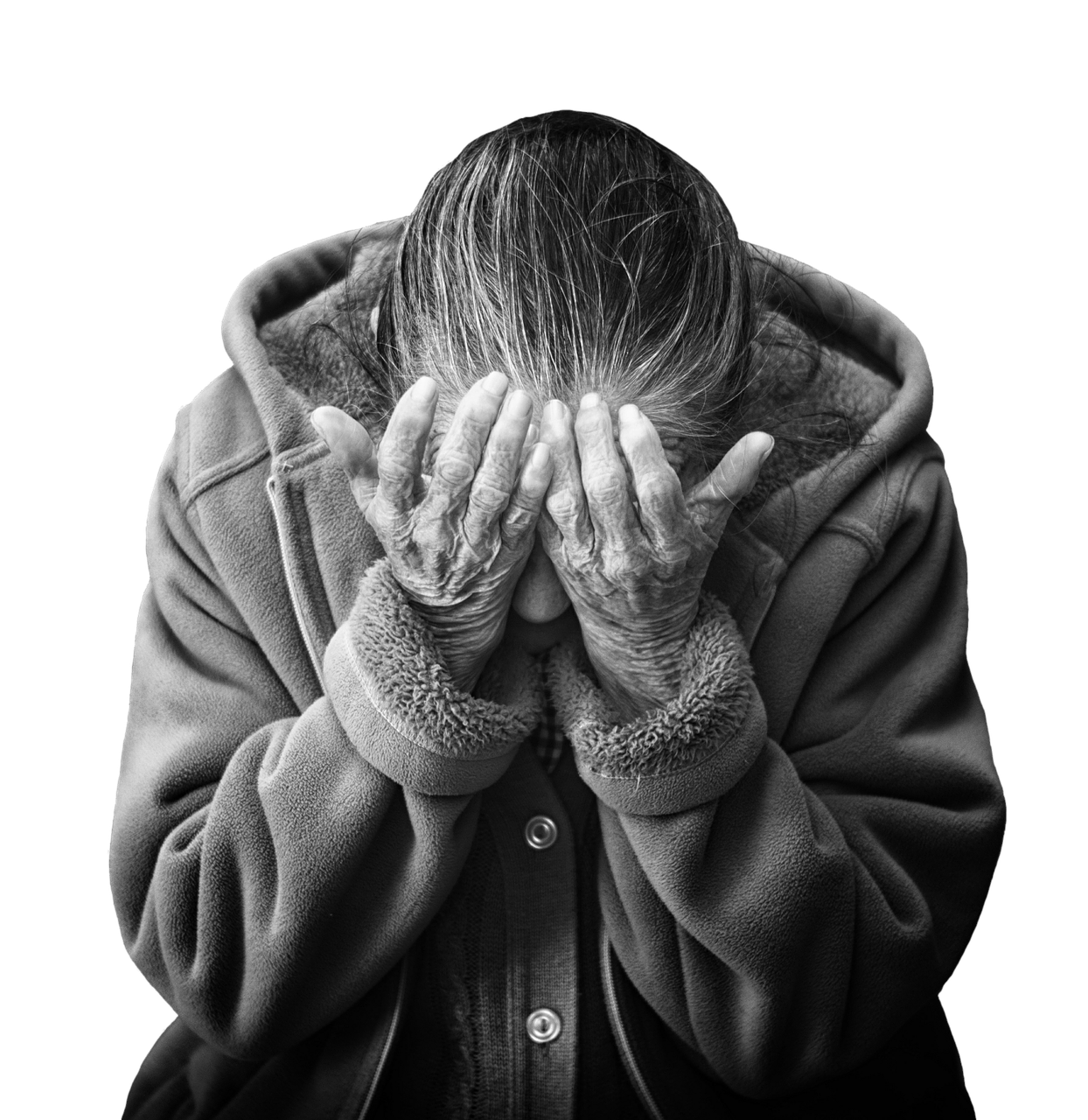

If there is one overriding stereotype about Christianity around the world, accurate or not, it is that, not only is Jesus the figure for whom we should hitch our deliverance on or, somewhat analogously as Buddhists would say, to take refuge in, but that Jesus’ own dominant focus was on the distressed, the forgotten, the sick, and the vulnerable which we should emulate in our own social relations. Or, to put it in terms of later Catholic Church doctrine, Christians must exercise a preferential option for the poor. This historical orientation has fostered a remarkable, overt identification of Christianity as a powerful force for rectifying social injustice. As the University of Notre Dame puts it on their website for the Center for Social Concerns,

As followers of Christ, we are challenged to make a preferential option for the poor, namely, to create conditions for marginalized voices to be heard, to defend the defenseless, and to assess lifestyles, policies and social institutions in terms of their impact on the poor. Preferential option for the poor means that Christians are called to look at the world from the perspective of the marginalized and to work in solidarity for justice.

From the Salvation Army to Liberation Theology. From the Catholic Worker to the Red Cross, the notion that Christians must reach out to those who are hungry, poor, in distress, and homeless, the marginalized or those wounded on the battlefield has been a major part of Christianity´s history. While Christianity´s failings are important to note, its generalized support of the genocide of indigenous peoples throughout the world, in Africa, North and South America, and Australia, and its selective and often ambiguous relationship to more modern-day tragedies such as the rise of Nazism, it´s successes in relief work and in outreach to the marginalized is historically well known and properly lauded.

When it comes to this notion of preferences, in Buddhism, by contrast, upekkha or equanimity, as one of Buddhism´s Four Immeasurable’s, is emphasized, which not only encompasses the individual non-preference for good or bad, fame or shame, rich or poor, but the Dharma´s profound vastness which explains the nature of things-as-they-are holding all phenomenal existence to be a compounded formulation akin to a dream, and the objects within that sort of dream, to be taken as ephemeral and thus, of little ultimate consequence. An important example is contained in this early teaching:

Just as he would feel equanimity on seeing a person who was neither beloved nor unloved, so he pervades all beings with equanimity.

(Vibhanga 275)

Let me say at the outset that I do not believe the Buddha meant anything here that should be construed as callous indifference to ordinary suffering. Nevertheless, what a religious teacher teaches, and what his or her followers hear, and act upon, are often at odds. By way of example, while I know Donald Trump suffers, from megalomania, from insecurities as large as his ego, etc. I also believe that the sufferings of the many homeless in New York City are more important and deserving of my attention. Or that the sufferings of the poor and near-poor throughout the US are more alarming, and MORE deserving of my attention than Bill Gates’ or Zuckerberg´s or Oprah´s or any other massively rich person whose lives have been gilded by the acquisition of enormous wealth in a system which rewards greed and condemns to poverty tens of millions. Because, what they are beneficiaries of is a system that enables certain individuals to amass inconceivable riches while countless others are condemned to lives of squalor and disenfranchisement. And while Buddhism extends its systemic lenses on a much wider framework of human suffering, the in-between area of the immediately near us is sometimes neglected. That in-between area is otherwise known as this Saha world in some texts, where we appropriately lament the ultimate pitiable state of all beings, but chalk it up to the ways of samsara. We jump from the immediate problem to its ultimate cause without stopping to investigate just what we can do to assuage the proximate causes here and now. We need to name this system. But we don´t. This, I feel, is a problem.

Let me say at the outset that I do not believe the Buddha meant anything here that should be construed as callous indifference to ordinary suffering. Nevertheless, what a religious teacher teaches, and what his or her followers hear, and act upon, are often at odds. By way of example, while I know Donald Trump suffers, from megalomania, from insecurities as large as his ego, etc. I also believe that the sufferings of the many homeless in New York City are more important and deserving of my attention. Or that the sufferings of the poor and near-poor throughout the US are more alarming, and MORE deserving of my attention than Bill Gates’ or Zuckerberg´s or Oprah´s or any other massively rich person whose lives have been gilded by the acquisition of enormous wealth in a system which rewards greed and condemns to poverty tens of millions. Because, what they are beneficiaries of is a system that enables certain individuals to amass inconceivable riches while countless others are condemned to lives of squalor and disenfranchisement. And while Buddhism extends its systemic lenses on a much wider framework of human suffering, the in-between area of the immediately near us is sometimes neglected. That in-between area is otherwise known as this Saha world in some texts, where we appropriately lament the ultimate pitiable state of all beings, but chalk it up to the ways of samsara. We jump from the immediate problem to its ultimate cause without stopping to investigate just what we can do to assuage the proximate causes here and now. We need to name this system. But we don´t. This, I feel, is a problem.

Apparently, HH the Dalai Lama agrees and is not afraid to, having spoken to this issue by calling himself a Marxist and saying, to the surprise of many of his wealthier followers:

The economic system of Marxism is founded on moral principles, while capitalism is concerned only with gain and profitability. Marxism is concerned with the distribution of wealth on an equal basis… as well as the fate of those who are underprivileged and in need, and it cares about the victims of minority-imposed exploitation. For those reasons, the system appeals to me, and it seems fair.

Elsewhere though, he describes the Buddhist view of non-preferentiality in more traditionally Buddhist ways, saying “it is essentially logical for us to train in cultivating an impartial attitude wishing for the happiness of all beings.”

That is, our impartiality should extend past our comfort zones of self, family, friends, tribe, race and continuing outward until it maximizes its expression to the highest degree, that of the Buddha´s admonition in the Metta Sutta “to regard all beings as a mother loves her only child”. This is not what is being criticized here.

Unfortunately, this broader, god perspective, if you will, an odd formulation given Buddhism´s non-theistic orientation, is so far removed from the object that its relevance, much like an ant you step on as you walk, is seen as of no or little consequence. Again, let me reiterate that Buddhism does NOT suggest that our lives, or any lives, are of no consequence, constantly promoting instead a widening circle of compassion which should be extended to all sentient beings. The non-prerequisite of vegetarianism notwithstanding as Buddhism is often more prescriptive over proscriptive.

However, in an effort to take the broadest view of Compassion, there appears to be way too much room for a casual dismissal of any proposed Buddhist preferential option for the poor and instead, a superficial rejection of individual or social justice concerns as not possessing the widest possible perspective of Compassion. Combine this with the earnest seeking of patrons to fund translations and schools, travel by high teachers, and the building of elaborate Buddhist temples and centers in the West, and there comes a problem tailor-made for more than just PR embarrassments.

This issue of Buddhism´s larger relationship to the poor and disenfranchised goes well beyond any East-West divide and at times hyper celebrity-focused orientation. There is the old question of, where are the Buddhist soup kitchens? I have been asking this very question since my early days as a Buddhist social activist and well into my period studying this very issue as an Engaged Buddhist, at the Naropa Institute (now Naropa University) from 1994-1997.

I´ll never forget the words of one classmate, an educated white male who left a thriving business to connect with Buddhism. He said to me, when I raised these types of questions, “Our intentions matter most in Buddhism and if there´s a homeless person, I will wish them well as I pass them.” To which I responded, “Have you ever thought of buying them a sandwich?” “My intentions are just as good” he answered, straight-faced.

I heard 3 years of that kind of garbage. And I still don´t buy it.

We are now living in a world that is literally burning up as the Buddha declared in his Fire Sermon, but in this case, it is not the passions, but the pollution and problems of industrialization that are causing this era of climate change. And as a result, millions of people are facing environmental disasters which are causing them to become climate refugees. In addition, there is a palatable rise in actual fascist movements around the world, in the Ukraine, in Poland, and yes, even in the US. In the Mediterranean, thousands have drowned seeking to escape constant wars in their homelands, and throughout South America, Asia and Africa, neo-liberal policies have unsettled social orders and destabilized countries, making our future not only unpredictable, but quite possibly unrecognizable. These issues disproportionately affect the poor, the underprivileged, darker peoples of the world while the West continues to spend gargantuan amounts of money and resources in military hardware and using them regularly, wreaking havoc throughout the planet, adding to and compounding these issues all over.

It is certainly noticed in the United States, for example, often, of course, by those who come from similarly marginalized, oppressed, and historically disenfranchised communities. The seeming contradictions between Buddhist doctrinal concern for an impartial compassion which works to alleviate suffering, and an apparently biased message directed to wealthier classes is being openly spoken of with some degree of attention. In a recent issue of Lion´s Roar, a well-known Buddhist magazine, author and Zen priest Rev. angel Kyodo williams wrote,

Thrust into the Western socioeconomic framework that puts profit above all, and coupled with a desire to perpetuate institutional existence at the expense of illuminating reality and revealing deeper truths, the dharma has become beholden to commodification, viewing it as inescapable and de rigueur.

Crucially she adds that,

What is required is a new dharma, a radical dharma that deconstructs rather than amplifies the systems of suffering that starves rather than fertilizes the soil that deep roots of societal suffering grows in. A new dharma is one that not only insists we investigate the unsatisfactoriness of our own minds but also prepares us for the discomfort of confronting the obscurations of the society we are individual expressions of. It recognizes that the delusions of systemic oppression are not solely the domain of the individual. By design, they are seated within and reinforced by society.

In all fairness, there IS an Engaged Buddhist movement with even universities offering degrees in this field (in fact, this writer received an MA in Engaged Buddhism in Naropa´s very first core class in 1997). And there are novel responses to novel crises being talked about and considered and, in the West, an awakening of Buddhist concern for issues of race and wealth, poverty and pollution, are all being considered. But there remains some serious questions about its focus which, 20 years after I left Naropa, are still not receiving enough attention.

So I´ll just throw it out a few of my questions here:

Why are so many of these Buddhists upper to upper to middle class Whites? Why are Buddhist temples in the West all too often centers of relief for the upper to upper middle class Whites who can afford to pay hundreds of dollars for teachings with great masters?

Can poor people benefit from mindfulness, chanting Amida´s name or the Nichiren chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, practicing Zen, or doing Tibetan visualization practices? Why aren´t they flocking to all these Buddhist centers which promise relief from suffering since, by all sociological measures I am familiar with, they suffer disproportionally more? Are they welcomed, encouraged, or even advertised to?

Can homeless people find benefits in Buddhist outreach? Maybe they need a place to sleep. Perhaps we can house them in all those Buddhist flop houses or shelters we build?

Why are Buddhist centers not located more among poor neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color? Why are all the dominant magazines about Buddhism (and while not exclusively Buddhist I would include this magazine as well) catering to, owned by, and made up of primarily upper to upper middle class White writers and basically directed to the same?

Does Buddhism have a poor or poverty problem in the West? Is it afraid to get in the trenches and to wash feet, feed and nurture compassion among those who just might need it, yes, I´m going to say it aloud, more than the wealthier groups who by and large fund those Buddhist dharma centers, temples and institutions?

Somehow those more systemic questions, along with many practical issues, and the many potential solutions seem to all get rapidly skipped over as attention is quickly turned to samsara´s deeper and apparently intractable misery. In my view, this betrays the bodhisattva spirit, for if we are, in fact, vowing to benefit (save) all sentient beings then our efforts should be directed at the ones right in front of us, right? It´s as if we are so focused on the horizon we fail to see what lies right before us.

Why is it that we think feeding the homeless, ending racism, or poverty in our local communities’ somehow too difficult, but we say we are committed to saving all sentient beings daily without irony?

We aim so high that, truth be told, we forget the suffering immediately around us or ignore it and jump instead towards a grander perspective which we are nowhere near but which sounds good and makes us look better. Thus, we are neither here nor there, locked into a dreamy vision bardo that insulates us from responsibility while granting us specious satisfaction that at least we are on the right track. After all, we always seem to find millions of dollars collectively to pay for visiting teachers and building grand stupas and temples and, oh well, you get my point.

I actually think we know the answers to these questions. Because simply put, Buddhism appeals more to the wealthier classes in the West from whom it gives a pass on issues of social justice.

One daren´t criticize one´s patrons who give hundreds of thousands of dollars regularly too much for fear of those very funds drying. And so we know, many of us feel within this terrible tension that the incredible Wisdom and Compassion message of Buddhism remains exclusively directed to only the most able and wealthy around us, who, not coincidentally, represent the same owners of the society who dominate its ruling classes and ensure a system which keeps the poor, poor and the marginalized away from our attention. This is a problem.

I´m worried. Because what should be a strength can instead be seen as a weakness, a way out in order to avoid difficult questions of actual, localized suffering while we instead solicit support from wealthy benefactors, referring to the state of those in poverty and at the receiving end of unjust systems as simply the effects of individual karma. If that sounds cruel, it most certainly is. And that´s another problem we need to face and address.