Must a dharma practitioner maintain a strict vegetarian or vegan diet? Were only the answer as simple as the question seems! But since dharma training is the continual development of wisdom and skillful means, to adequately answer this question, we must carefully and systematically study core teachings on preserving and integrating the three levels of vows; on expedient vs. definitive instructions; and on proper coordination of conduct, motivation and view.

First, to understand how the three levels of vows co-exist and support one another, we should study, for example, classical treatises like A Clear Differentiation of The Three Codes, by Sakya Pandita; Jigme Lingpa’s Treasury of Precious Qualities; and the relevant discussion in Longchenpa’s Chariot of Purity, his auto-commentary on Resting in Meditation. These and other expert commentaries expressly address topics like consumption of meat and alcohol.

In an important sense, all of these teachings elaborate upon, and never depart from, the Buddha’s root instruction to refrain from causing harm; perform marvelous virtues; and thoroughly tame our own minds. Whatever promotes harmful or reckless conduct, is dismissive of virtue, or tends to inflame or perpetuate the power of mental disturbances and wrong views, is not the teaching of the Buddha. Period.

The vows and trainings of the vehicle of individual liberation, the general, foundational vehicle, primarily are focused on the first of these points, proper discrimination between what helps and what harms; though all certainly are included. The principal afflictive mental state to remedy here is aggression. The principal approach is to modify and control one’s conduct of body, speech and mind. If you cannot calm down, discriminate clearly between what is helpful and harmful, and modulate your conduct accordingly—the trainings in samadhi, prajna, and sila, respectively—your life will not become a path of conforming to what is true and beneficial, i.e., the dharma.

In this context, not eating or using animal products seems a straightforward path to avoiding causing harm to other living beings. But, to make an awkward pun, this is only the first cut. You are definitely on the path, but exactly how far can this rule and this vehicle alone carry you? Because of the operation of interdependence and karma, which are largely beyond the range of control of one’s expedient behavioral choices and decisions, conduct modification, although a necessary foundation for all other practices, is an inherently limited and imperfect approach to avoiding harm.

One can live in a tree, wear a breathing mask, carry a whisk to clean the ground before one’s feet, eat only nuts and berries, and so on, and still never be able perfectly to practice the precept of avoiding causing any harm to other living beings. Even if one is vegan, beings inevitably are harmed in the process of delivering fruits and vegetables into one’s mouth. No matter what labels are applied to our food products—cruelty free, organic, free range, and so on—none are or can be entirely harm-free or death-free.

Moreover, beyond food choices, one may purchase unrelated products from diversified companies whose food divisions support the slaughtering of animals. One may keep pets and feed them meat products, or shelter them while they hunt and kill other animals. One may drive a car whose windshield is a summertime slaughterhouse, and which depends on one or another form of energy generation that causes harm to living beings and their habitats. One landscapes, plants flowers, or mows the lawn, or turns on electric lights at night that attract and kill insects, or does any of a hundred other unskillful actions each day that contribute to the suffering and demise of other creatures, even if inadvertently, or directly contrary to one’s best abstract intentions.

It is not the case that one should therefore be less discriminating in one’s actions. In fact, doing one’s best to limit the harm footprint one makes by living in this world is an indispensable first step. One must, however, eventually recognize the fundamental limitation of this approach to liberating oneself and others from suffering and the causes of suffering, and look deeper.

The bodhisattva vehicle of training is based on a deeper and broader appreciation of the inter-relationship of the two truths. That is, the unity of interdependent appearance and emptiness becomes a prime subject of investigation and contemplation. Motivation overtake conduct as the principal driver of spiritual practice, and skill expands and sharpens beyond measuring conduct against a checklist of approved or disapproved choices, to encompass the transcendent virtues. The training has more to do with how you approach situations, and why you do what you do.

At the broadest level, in this vehicle one fully assimilates the truth that collectively we have already chosen, by the operation of karma, to manifest and act within a world that ineluctably is not harm-free or harmless. This is the suffering that pervades composite structures, samsara. It cannot be fixed on its own terms, because its terms are deficient—degraded, degradable, and degrading. No matter how careful we are as consumers and political agents, we will not turn samsara into nirvana. Seeking to educate every single being to make correct choices is excellent and necessary, but not sufficient to fix the problem. Even if by pulling together we could turn this human world we share into a replica of a god realm, well, what then? How will we get the birds, fish and insects to stop eating one another?

With a motivation to be of maximum benefit, and greater wisdom into the interplay of causes and effects on multiple levels, rather than categorically shun all actions which, on their face, might inflict harm, one may elect to take on the karma of causing limited harm, in order to alleviate suffering on a greater or more lasting scale, or a deeper level.

The traditional example from a previous life of the Buddha, when he was a bodhisattva advancing along the paths and grounds, is that of the merchant who killed a prospective murderer before he could assassinate 500 bodhisattvas; but there certainly are many examples closer to home. Controlling insect or animal populations in a finite ecosystem, so that they neither overrun the system nor end up bringing famine upon themselves, might be one such example. Anyone who has done a lot of life ransom practice, for that matter, knows how difficult it can be to calculate whether one’s interventions will be net protective or destructive of life in the short or long-term. So, saving all life is not the final point of life ransom practice.

Taking life is no longer regarded as inherently the wrong choice in every situation, depending upon motivation and the application of skillful measures. And compassion for the inevitable suffering and loss of life that comes to all those born through karma into this interdependent network of living being becomes both indispensable and paramount. Saving a life is not enough. It is temporary, and no guarantee of lasting or short-term wellness for the one saved, or those other beings to whom it is connected. Only the liberation and enlightenment of all beings can ever be enough.

If the first vehicle emphasizes conduct, and the second, Mahayana, is primarily concerned with refined motivation and intelligence, and skillful implementation of action, then the heart and soul of the third, secret mantra, is training in the view. What view? As the master Mipham explains at length in his seminal overview of the Guhyagarbha Tantra, itself the seminal expression of tantric outlook according to the Nyingma tradition, the view is universal purity and equality. This view is the basis, path and result of secret mantra practice.

No matter how phenomena might appear to a mind bound within the grip of deluded grasping and fixation, by their very nature they are completely pure, empty yet apparent expressions of fundamental bodhichitta, or buddha nature. Nothing is inherently impure, and therefore nothing finally is to be rejected, in order to realize the enlightened state.

On the contrary, one must deliberately train in overcoming limited and limiting conceptions of every stripe. One does so for the very same purpose one also trained in discriminating conduct and refined motivation—to forever rid oneself and others of suffering and its causes. The Buddha said that he taught illusory dharma to teach illusory beings how to rid themselves of illusory suffering once and for all.

The view subsumes all conduct, meditation, and motivational training, yet never excuses lack of skillfulness. It does not forgive indifference to causing harm, or indifferent motivation. In this sense, the higher view does not contradict or supersede the guiding principles of the other vehicles. But that doesn’t mean the logic of avoiding harm and performing benefit doesn’t evolve.

Karma’i Khenpo Rinchen Darjay, in one detailed instruction manual, explains, for example, that a root vow of tantra requires one to take life. The life force that one must cut off, however, is the mind’s false projection of an independently existing and self-interested ego—call it rudra, or mara, or the demon of inflation, as in the chod practice tradition. Its sticky appearance must be disrupted through the yoga of self-visualization as an enlightened deity, its life force must be suppressed and transmuted through energy yoga, and the unaware grasping and fixation upon which its continuing display depends must be excised through ati yoga meditation.

Through one’s view, and through the application of mantra, mudra and samadhi in the context of two-stage yoga, one transmutes and readily consumes all false appearance of things as inherently attractive or repugnant. This is the feast substance, and it encompasses all one’s perceptions, not just the faculty of taste. Thus, the Guhyagarbha Tantra enjoins tantric practitioners to consume meat and alcohol as feast substances. These represent our passions and reified perceptions, grounded in ignorance. It is ignorance that must be consumed by wisdom, and its manifestations ultimately enjoyed as the pure expression of wisdom, nothing more and nothing less. To enjoy the feast of sensory and mental experience, transformed into the pure display of wisdom essence, does not mean that we revert to forms of conduct and motivation that are in conflict with other levels of ordination.

Thus, Rinchen Darjay explains that the five meats and five nectars are not only chosen because they are substances that are repugnant according to conventional tastes, but because the meats, for instance, belong to animals whose lives are never taken by pure-minded persons in order to have food. Thus, to be used as feast substance, they had to have died by natural causes.

Arguably, in the modern, global economy, where karmic connections among living beings are both highly attenuated and complex, picking up a small packet of meat in the supermarket is virtually, although not perfectly, tantamount to collecting road kill. It is possibly the next best thing. A nice pork chop for those indoctrinated in Judaism and Islam, a nice beef steak for a Brahmin, chicken for human cannibals, and so on. Here an objection can be raised: if we buy a piece of meat, doesn’t the supply-chain economy react to replace it in the grocery aisle, where it otherwise would not?

If hundreds of tantric Buddhists shopped in the same Whole Foods outlet, perhaps that would be the case. But if we relatively few tantrikas are thoughtful and selective, we not only are very unlikely to add to the toll of lives lost to consumption of meat by our twice-monthly small purchase, but likely will be substituting our purchase for that of another person who lacks our motivation and purpose in forming a compassionate and aspirational karmic connection with the being whose flesh has been slaughtered. If you feel that even this much impact is too painful to bear, another option is to simply add dutsi mendrub to vegetarian feast substances, knowing that it was produced with ingredients that fulfill all necessary requirements.

In any case, training in the view of secret mantra by visualizing the transformation of the flesh of that being into pure wisdom amrita, consecrating it by application of dutsi nectar, mantra and samadhi, and dedicating, with heartfelt bodhichitta, the merit of the assembled feast practitioners, along with all other merit, to the short-term rebirth prospects of the being whose life was associated with that flesh, and to its long-term enlightenment, sealed by the aspiration to serve as a guide to that being in all lifetimes, undoubtedly is a higher form of virtue than viewing the rent flesh of that being as inherently repugnant, and refusing any association with it. Taking it into one’s own body with proper motivation and view is an assumption of an incredibly profound responsibility, and an act of true love.

Without such an understanding and view, of course, the act of consuming meat, with, at best, indifference to the welfare of the being from which it was drawn, can accomplish little more than impede one’s cultivation of bodhichitta at the mahayana level. At worst, it can accomplish great harm.

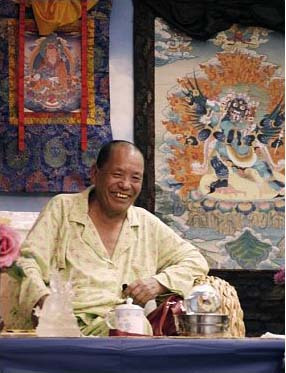

Once, my teacher Orgyen Kusum Lingpa, after bestowing an empowerment of Avalokitesvara in San Diego, gave the samaya of refraining from eating meat as part of one’s regular diet, because, he said, eating meat destroys our training in bodhichitta. Some smart person in the audience raised his hand and said, “But Your Holiness, you eat meat!” Kusum Lingpa, without missing a beat, retorted, “I said training in bodhichitta. When I eat the flesh of a being, that being only benefits!” And so it was with Tilopa, with Do Khyentse Yeshe Dorje, a root guru of the vegetarian and highly fastidious Paltrul Rinpoche, and other siddhas.

So what should one do if one nominally is an empowered tantrika with secret mantra vows, but honestly can’t partake of the feast substances with pure view, despite one’s best efforts and intentions? Try your best to approximate the view, even if just conceptually, and perform apologies and confessions to the deities, in the fulfillment section of the feast, for any transgressions.

To repeat an important point: To guard one’s precepts and spiritual commitments at all levels, one must respect each level of practice on its own terms. Thus, there cannot be an ordained sangha, according to the general vehicle, unless the vow to abstain from causing harm is respected. The formal receipt of higher levels of ordination should never be treated as an excuse or pretext to disregard this foundational precept of the Buddhist path.

Thus, when a rampant and degenerate practice emerged of reveling in the consumption of meat and alcohol during feast practices, with passion, aggression and indifference to life not at all transmuted by wisdom or transformed through genuine compassion, and when such practice reflected badly on the sangha and the tradition of Buddhadharma, it was a highly skillful command by His Holiness the 17th Karmapa, albeit contingent and provisional, to suspend all consumption of meat at feasts by ordained sangha, until this rampant misconduct had been rectified.

To be clear, while the basis of this command was the monastic precepts of the vehicle of individual liberation, it was also perfectly motivated by the bodhisattva precept of preventing beings from further harming themselves and others through corrupted practices. And, when issued by one with perfect wisdom, like His Holiness the Karmapa, it also sprang from the view of great purity and equality that is the seal and samaya of secret mantra.

Under other circumstances, observing this command would be a fundamental breach of samaya by those capable of following the tantric path and its precepts. I do not believe for a moment that the Karmapa would deny this, just as I am confident that the previous Karmapa, living and acting in different times and working with different circumstances, did not see fit to proffer the same instructions and was no less wise or compassionate than his successor for it.

Holding a perfect view of a realized guru is the root of all methods for realizing the view of all-encompassing purity and equality. Some accomplished gurus appear to eat meat; others appear strictly against it. As the story goes, when Kalu Rinpoche used to have lunch with Chatral Rinpoche, the former, a meat-eating monk, fed the latter beans and vegetables, and the latter, a strict vegetarian layman, fed the former meat, each with devotion to the other. What each revered in the other was genuine wisdom imbued with unbiased and unbounded compassion, and each lacked the slightest thought that the conduct of the other was in any way impure.

In short, one must understand not only each level of spiritual vow and practice on its own terms, but also how they fit together in each situation. Beyond this, and even more important, one must proceed in a way that is true to one’s own actual level of practice, and never be hypocritical or insincere. Nor should one be complacent, or refuse to entertain the possibility of enhancing one’s practice of bodhichitta through cultivating a higher view. Such stubbornness, pride, or rigidity is also problematic. To seek out vajrayana or dzogchen teachings, for example, while adopting only those principles and practices of vajrayana that fit neatly within one’s own preconceptions and limited view, is a recipe for disaster, to make another weak pun.

The eleven principles of tantra elucidated by Mipham in his treatise on Guhyagarbha Tantra—mudra, mantra, offering, conduct, view, meditation, mandala, activity, practice-accomplishment, samaya, feast—are not an a la carte menu. As he explains, they interpenetrate; each includes all the others. We can say they are mutually implicative. They are the magical tapestry of reality, and it is the tantric view that weaves this tapestry together.

For example, samaya is about observing what supports the view, protects it, and enables one to cultivate it more fully and deeply. Samaya is not someone else’s command or punishment. It is what your true nature requires your apparent nature to commit to, in order to reconnect fully with that true nature. It is anything but a fundamentalist belief to which you must subscribe, if you seek permission to enter the gates of vajra heaven.

The view of secret mantra is not a dogmatic or moralistic belief. No one is asking anyone to believe anything. Beliefs are not only beside the point; they are an obstacle to the view. Religious dogmas depend upon fixating the mind through the force of hope and fear. Hope of reward, fear of punishment. The view of secret mantra is beyond hope and fear, and the training is to see through to the essence of hope and fear as they arise in experience. Challenges to one’s habitual ways of giving rise to hope and fear are welcome, they are the fuel of this path.

Feast practice, among other things, is designed to reveal the nature of, and to liberate our responses of attraction and rejection toward sensory perceptions of the offering substances. In fact, we should enjoy both very desirable and very undesirable things at a feast practice, not just one or the other. To do this, we first must have been empowered, and have recognized what is being pointed out or introduced in the empowerment process. For instance, there is a stage in the empowerment of the goddess Marichi, a form of Tara, in the treasure cycle of the Heart Essence of Padma of His Holiness Orgyen Kusum Lingpa, when one alternately is exposed to both extremes in relation to each sense gateway. For tactile sensation, first a feather, and then a piece of sandpaper is rubbed against your cheek.

If you want to realize the view in which awareness and basic space are a fundamental unity, you may be required, at some point, to jump out of your conceptual airplane and experience the rush of all of space against your naked mental membrane. No one will push you out against your will. Having the thought, after you jump, that you wish you had a mental parachute, or that you wish you had learned to operate your mental parachute, or that your mental parachute is the wrong color, or the instructions on it are in the wrong language, will not serve you well.

This is what we mean by the dangers or risks of vajrayana. The entire path is by your mind, for your mind and in your mind… wherever that is! You have to trust in the operation of awareness without a dualistic, conceptual safety net, relying only on the built-in safety manuals of samaya, devotion, and so forth.

Thus, to judge a tantric preceptor solely according to the parameters of monastic precepts or generalized rules of conduct, or, conversely, to measure the quality of all levels of preceptors solely by reference to their willingness or eagerness to engage in tantric conduct that appears to transgress conventional boundaries, only invites confusion, and will create lasting obstacles to one’s own spiritual growth. You simply can’t tell for sure what the conduct of another practitioner, including whether or not they eat meat, indicates about their level of spiritual practice. But you must be sure about what eating meat means for you.

This has been just a concise presentation of a very rich and profound topic. I apologize to my teachers and to the dakini guardians of tantric samaya to the extent I have failed to express their intentions properly, or to implement them properly through these words. May all beings benefit.

Featured image by Ulla Koch, Denmark and her FB link for vegan posters.