An Ancient Location…. The absolute emptiness of space expresses itself spontaneously in an infinite array of worlds, worlds more varied and numberless than all the oceans of galaxies of stars. Space itself, empty of causes and characteristics, manifests directly as trillions upon trillions of universes. Their worlds all exist simultaneously and interpenetrate one another. This view was first developed in China in the Buddhist tradition that emerged from the Avatamsaka Sutra in the 3rd Century AD. As has been said: Worlds upon worlds now move like seas of atoms, passing through the limits of time, dimension, life and death.

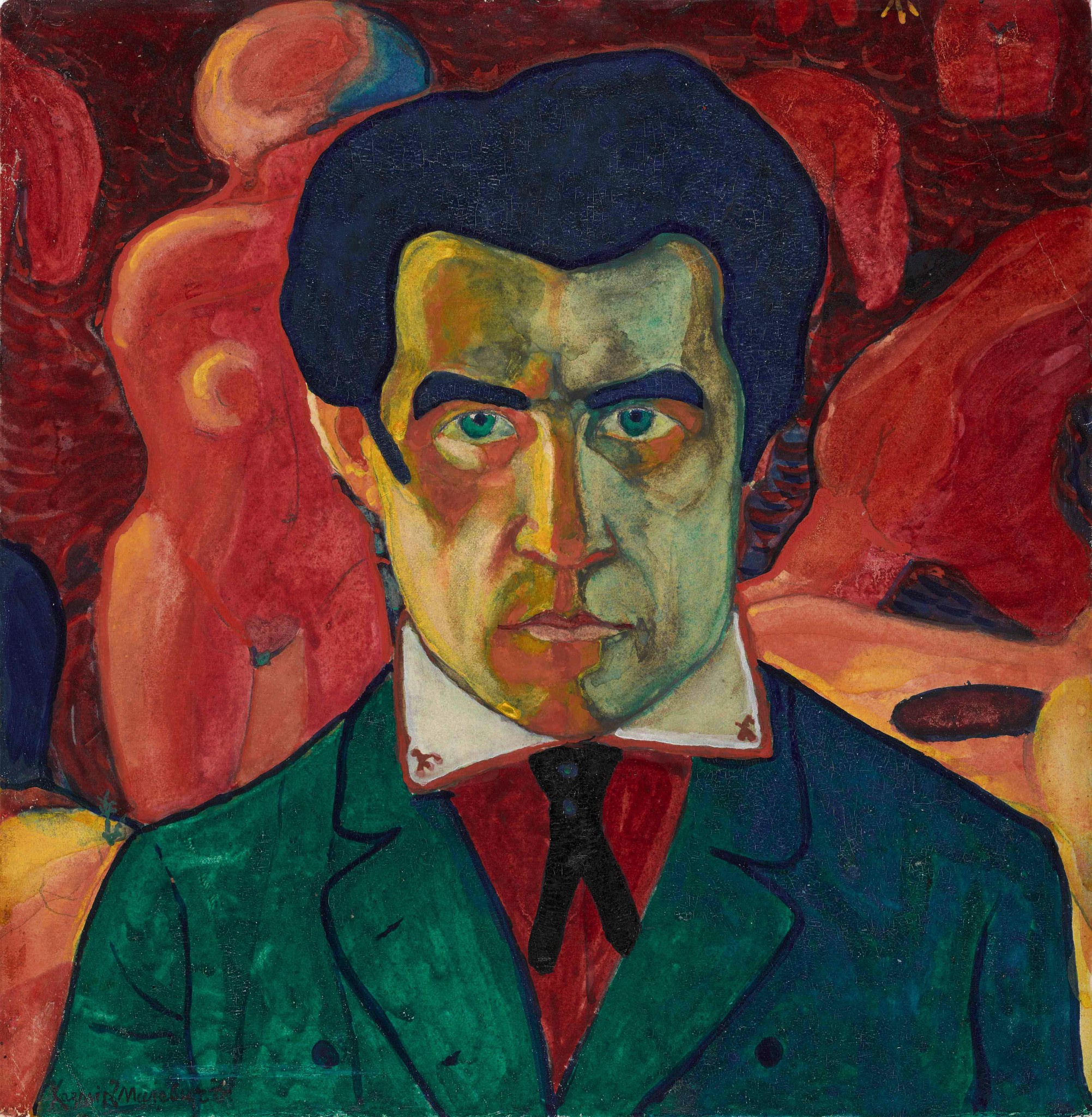

A Later Explorer. In the second decade of the 20th Century, Kazimir Malevich began the exploration which he called Suprematism. He began with the insight: “It is from zero, in zero that the true movement of being begins.” Here are some excerpts from his Suprematism Manifesto: “By suprematism, I understand the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist, the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, quite separate from the environment in which it is called forth.”

“To the Suprematist, the appropriate means of representation is always the one which gives fullest possible expression to feeling as such and which ignores the familiar appearance of objects.” “Feeling is the determining factor and thus art arrives at non-objective representation, a new world, the world of feeling, free from the ballast of politics, religion and their constructed objectivity” “The familiar recedes ever further and further into the background. The contours of the objective world fade more and more, step by step, until the world, ‘everything we have loved and by which we have lived’ becomes lost to sight.” “No more likenesses of reality, no idealistic images, nothing but a desert. But this desert is filled with the spirit of non-objective sensation which pervades everything.”

Now, entering this gateway that Malevich opened a century age, three contemporary Hungarian artists, Balint Szombathy, Aniko Robitz, and Minyo Szert have been exploring the worlds hidden within the surface of perceptual phenomena. In very different ways, using fixed images derived from photographic and telephotographic processes, they uncover and give us new and very different worlds. Some of their haunting and mysterious work has been brought together in the Photon Gallery exhibits titled Photosuprematists.

In his wide-ranging career, Balint Szombathy has, as Misko Suvakovic noted, “built a strategy of critique, subversion and even deconstruction of cultural and national canons and the expected role of art in societies in which he lived.” He has presented the suddenly undomesticated, unsettled and unsettling social spaces that emerge when changes in context shift the meaning of political images.

Szombathy has wandered like a flaneur through the less favored parts of cities, gazing at gestures of abandonment and loss. He has presented them in the photographs collected in Városjelek (Signs of The City). Here he gives us traces of forgotten actions left by the city’s occupants as they modified the much larger organism to their smaller purposes. That these marks have remained is unintentional. They are simply the gestural residue of people trying to lead a private life. What they have left are anonymous, temporary and accidental marks on the city’s skin, marks that hint at people’s presence and struggle but nothing else. There is no clue to anything personal. Passions, beliefs, hopes, anxieties are not to be found here. Nonetheless, these omnipresent markings give depth and texture to the city’s surface as they point silently to the density of life in time and to the innumerable small and secret worlds within a larger and more indifferent one.

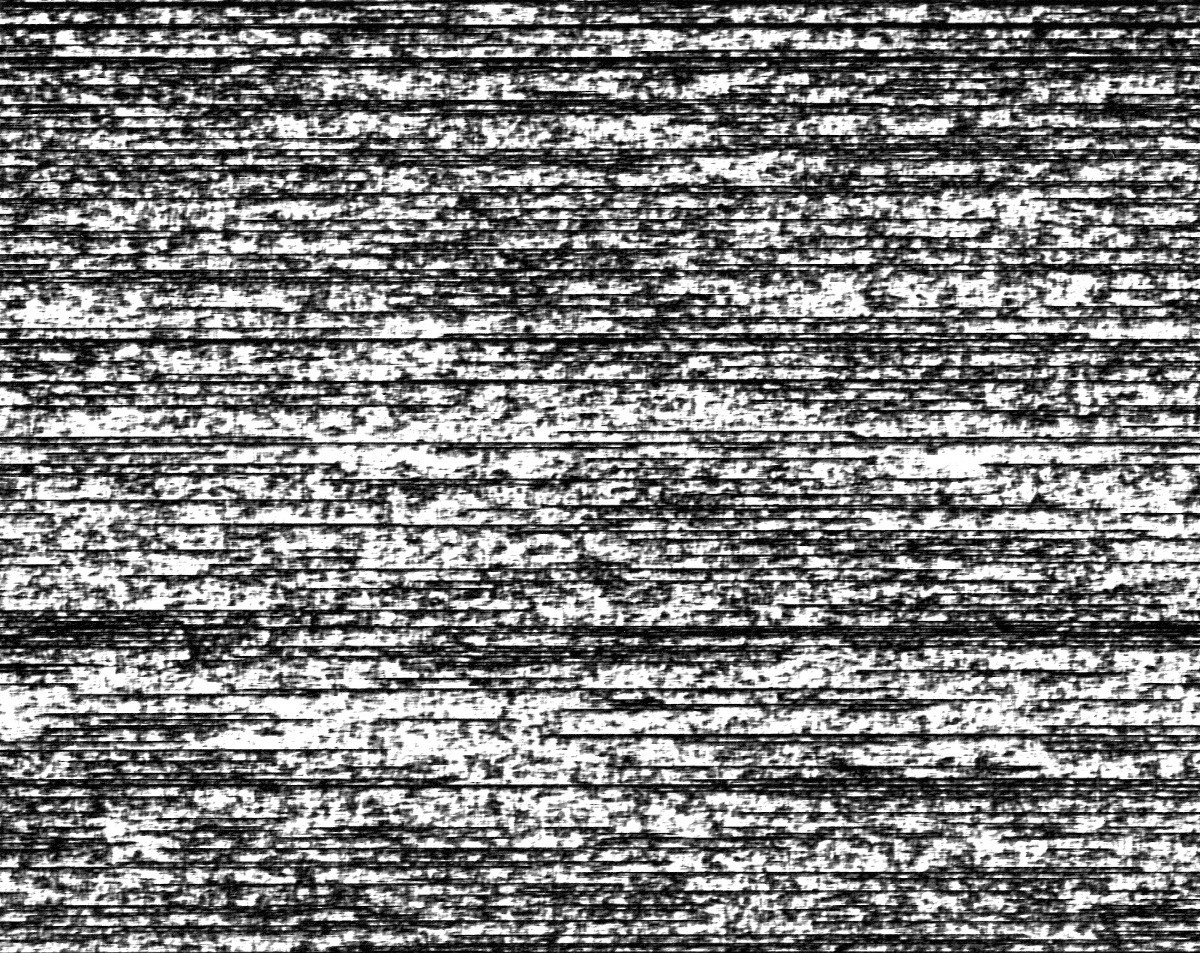

In the work on view in the Photosuprematists exhibit, Szombathy gives us further images from a different dimension of secret and forgotten life. These are electro-photographic images, accidentally generated when there were errors in transmitting photographs via analogue fax machines. He found hundreds of such unreadable images in the waste paper of a regional newspaper.

Inherent in all communication are moments and gestures that are essential to the functioning of communication itself but incomprehensible to sender or receiver. In these images, that aspect of imperfect connection is revealed when something in transition has been arbitrarily and unintentionally stopped. The image is no longer what one knew but is not yet what is intended. So, in some ways, these images correspond to Duchamp’s stoppages. They are a visual display of something in the process of change. They were never intended to be seen. They are rescued evidence of the secret realm of what Trungpa Rinpoche called the subconscious gossip that continually underlies our communication altogether.

Anikó Robitz was born in Hungary where she lives and works. But she spends much of her time travelling the world, visiting famous and less-well known cities. Among many other places, she has wandered in Tallinn, Sydney, Madrid, Bilbao, Niagra Falls, Graz, Strasbourg, Vieques, Puerto Rico, St. Jean de Luz, Berlin, Reykjavik, Paris, Venice, Hanoi, Tirana, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Kyoto, Livorno, Zurich, Madrid, Damascus. With patience and unique discernment, she has searched for things there, invisible to the eyes of the resident or ordinary tourist.

Guided by a unique optical sensibility, or a sensitivity to what Malevich called, the spirit of non-objective sensation which pervades everything, Robitz sees something new in the chaotic geometry of contemporary urban landscapes. Her art derives from seeing without pre-conceptions. In the small passages from one plane to another, in various kinds of architectural transitions, she finds a miniature world of beauty.

Her photographic methods are quite direct; she does not take a multitude of images, nor does she have to discard innumerable out-takes. The images themselves are enlarged but otherwise not manipulated in any way. In her pictures, she gives us the hidden world that she sees. We cannot tell that these are parts of buildings or shadows made by buildings. We cannot tell whether the buildings are old, new or under construction. There is however nothing that suggests the atmosphere of the cities where the pictures were made. In fact, Robitz has said that the names of the cities have been attached to the pictures only at the request of the gallerists. Nonetheless some of the imagery that emerges seems close to Malevich’s own circles and squares, while in other pictures the lines and grids, shadows, patterned surfaces evoke an aesthetic of geometric abstraction. The pictures she gives us have a poise and quiet harmony, a kind of beauty that is accessible but not obvious. They exhibit balances, rhythms and contrasts that are completely their own.

These are the secret and hidden beauties of a completely man-made world. They are not the result of erasures or alterations made by time. They do not refer to change or loss. They are worlds hidden because the builder’s eye, as well as that of the occupants, has been focused on larger effects or more ordinary usages.

The Budapest artist-photographer, Minyo Szert described the beginnings of his journey and his process: “I graduated from the School of Photography in Budapest, but I did not want to be a photographer. Nor did I want to be a cameraman. When the photographer takes a picture, the work is over; while my studio work starts at this point. I work in this thin line where photography and painting meet.” Minyo sometimes uses nostalgic images from old photographs: a couple swirling by as they dance, a table set and waiting, metal folding chairs, a parked bicycle, people sledding on a winter hillside, a doorway, a man spying on his neighbors, a summer landscape. On other occasions, he photographs the stairs by the Danube, a woman descending into the subway, details of the Berlin Holocaust Memorial. These images, fixed moments in the near or distant past, are the beginning.

In a photograph, it is always assumed that the picture’s ground, the emulsion on paper, or whatever other backing, will have an industrially perfect evenness and will be utterly unobtrusive. But here Minyo intervenes. He is, as he describes himself, a freehand photographer. In spontaneous and subtle strokes, he spreads the ground of photosensitive emulsion and creates a painting beneath the image that interrupts it. This process makes each piece into the meeting point of an image fixed in the past but infinitely reproducible and a completely spontaneous, unique and living gesture.

It is in these junctures of the fixed past and the fluid unpredictable present that Minyo finds the new worlds that he offers us. These are worlds that exist more in time than in space. When images that evoke a momentary past merge with textures and gestures produced with immediacy on the spot, we find ourselves in a place that is neither there nor here. We are not seduced into the past and we are not responding directly to the present. We are in between. It is one of the mysteries of Minyo’s art that the worlds he discovers and shows resist placement. He gives us a different dimension. It is unsettling but enticing. Moving through the superimposed present and past, we move back through the images and gestures to a world where objectless feeling has a purity and immediacy we could never have expected. Not graspable, not even quite describable, Minyo evokes in us a living quality of intuition in worlds that emerge with the directness of a brush stroke and the persistence of a memory but are, at the same time, completely free.

Featured image by Károly Minyó Szert.