As a writer, I’ve always felt a strong interest in the personal lives of other writers whose work I admire. Among my favorite writers, especially during my younger years as a freelancer in Asia, was John Blofeld, whose books helped inspire my early interest in Buddhism and Taoism and fired my imagination with colorful visions of life in China before the communist revolution swept away traditional culture there.

As a writer, I’ve always felt a strong interest in the personal lives of other writers whose work I admire. Among my favorite writers, especially during my younger years as a freelancer in Asia, was John Blofeld, whose books helped inspire my early interest in Buddhism and Taoism and fired my imagination with colorful visions of life in China before the communist revolution swept away traditional culture there.

I’d always imagined John as an eccentric old scholar long retired from his Asian travels and living a reclusive life in his native England. So when in 1986 I heard from a journalist friend on assignment in Taipei, where I was living at the time, that John Blofeld lived right nearby in neighboring Bangkok, I decided to go there to visit him. The journalist, who’d had dinner with John in Bangkok the previous week, gave me his address, and I immediately wrote him a letter expressing my longstanding admiration for his work and my sincere wish to meet him. He delighted me with a prompt reply, thanking me for my letter and inviting me to come visit him at the House of Wind and Cloud, his home in Bangkok

John Blofeld was born in England in 1913. One day when he was still a little boy, his favorite aunt took him out shopping. As they passed by an old curiosity shop, something that would ultimately mold his mind and steer the course of his life caught his eye: it was a small Chinese statue of the Buddha. He hadn’t the slightest notion what it was, nor did his aunt, but it captured his heart and he knew with absolute certainty that he must have it. Tugging his indulgent aunt into the shop, he made such a fuss about it that she finally relented and bought it for him as a gift.

Treating it like a treasure, he took the little statue home and reverently placed it on his bureau. Soon he realized that simply gazing in silence at this image of the seated Buddha engendered extraordinary feelings of peace and tranquility in his heart. Later, when he learned from a book what the statue represented, his devotion grew even deeper, and he began placing offerings of incense and flowers before it, secretly becoming a closet Buddhist.

After two years of studies at Cambridge, the call of the East beckoned him with such urgency that he ignored his family’s pleas to stay and finish his university degree and instead boarded a ship bound for Hong Kong, where he landed in 1932 at the age of 19. There he taught English and studied Chinese, biding his ti

me while he waited for a chance to enter the Dragon Gate of China, the fabled land of his dreams. After several false starts, his chance finally came when a Chinese friend arranged a teaching post for him in Peking. And so in 1934, at the age of 22, John’s childhood dream came true. Passing through the gigantic gates of Peking, he joined the privileged ranks of residents in the fabulous old capital of imperial China.

Later in life, long after the strife of war and revolution had spoiled his dream, John wrote a poignant memoir of his early days in Peking and called it The City of Lingering Splendor. For me, as a sinophile who went to Taiwan with the same dreams of China at the same age as John when he went to Peking, this book and its charming depictions of traditional Chinese ways that have vanished from the world reveal the magnitude of the loss which my generation of China hands suffered when China’s colors shifted from imperial gold to revolutionary red.

Shortly before Mao’s army stormed into Peking, John married a Chinese lady and escaped to Hong Kong.

“Why Hong Kong rather than Taiwan?” I asked him during one of our long talks at the House of Wind and Cloud.

“Because at the time,” he explained wistfully, “we were all convinced that soon Taiwan would be swallowed by the same red tide that engulfed China.”

Flat broke with a wife and two infant children to support, and not yet a writer by profession, John accepted an administrative position with a United Nations organization in Bangkok, and in 1950 he moved to Thailand. “One thing led to another,” he told me, “and I’ve been living here ever since.”

By the mid-1950s, John’s literary inklings began to stir, and he started writing books about his travels in China, focusing particularly on his lifelong spiritual quest, his pilgrimages to sacred mountains and remote monasteries, and his frequent encounters with Buddhist monks, Tibetan lamas, and Taoist hermits. When his wife took their two children and moved to England a few years later, John became a recluse and devoted most of his time and energy to the cultivation of his spiritual practices and cultural interests, and to the writing of his books on Buddhism and Taoism.

The Tantric Mysticism of Tibet, The Gateway to Wisdom, Taoist Mystery and Magic, Beyond the Gods, The Zen Teachings of Huang Po, Bodhisattva of Compassion, and other inspirational books on the spiritual traditions of the East flowed from his pen, introducing a whole generation of Western readers to the wonder and wisdom of ancient Asian mysticism. Despite the esoteric nature of his material, John always wrote with lucid clarity and cogent sense, in a style both elegant and intimate, anecdotal yet authoritative. In his later years, he summed up his life and his spiritual discoveries in The Wheel of Life: The Autobiography of a Western Buddhist.

I’d never been to Bangkok before, so when I arrived there to visit John in March 1987, I had no idea what this smoldering city held in store for me. On the one hand, I’d come to pay my respects to a literary elder and fount of spiritual wisdom. On the other hand, the lyrics to the song, One Night in Bangkok, kept running through my mind as the plane glided in for a landing, because a few days before I left Taipei, by some strange twist of fate, an editor telephoned me from Hong Kong and offered to fly me to Bangkok to write a short guide to that city’s notorious night life, all expenses paid. A young freelance writer living on a shoestring budget is in no position to refuse a well-paid assignment, and so I accepted.

As I approached the House of Wind and Cloud for the first time, my immediate impression was, “It looks like a temple!” It sounded like one too, with Chinese chimes ringing in the breeze from the swooping eaves. Splendidly perched on stilts in a Chinese garden, with steeply peaked rooves etched gracefully against the blue sky, stood a traditional Thai house built entirely of polished hardwood and glazed tile, without a trace of metal or concrete. This was the first time I’d ever seen a real Thai-style house, yet somehow it all looked so familiar to me, like the Buddha in the old curiosity shop felt to John when he first set eyes on it. As I rang the bell at the gate, I said to myself, Some day I must live in a house just like this.

The maid let me in and showed me upstairs to John’s room. I’d called ahead to announce my visit, so I knew that he was expecting me, but when I entered the inner sanctum where he wrote and slept, I was surprised to find him lying flat on his back in bed.

“Come in, come in, Dan, have a seat here beside me,” he said, sitting up and greeting me like an old friend.

“We have so much to talk about.”

He rang for the maid and told her to bring a kettle of hot water so he could prepare Chinese tea for us in the room, and mentioned briefly and unemotionally, as though noting the weather, that he was dying of cancer. Then, without any further formalities, we launched into a lively talk about China and things Chinese.

And talk we did! All afternoon and into the evening we ranged across the length and breadth of Chinese history and civilization, pausing here to examine a favorite period or poet, there to analyze an ancient anomaly or debate a simmering historical issue, discussing everything under Heaven like two old friends in China might have done a hundred years ago. I signed a copy of my book on traditional Chinese medicine for him, and he in turn autographed a few copies of his books for me, including my favorite, Taoist Mystery and Magic. Our taste in things Chinese ran in remarkably similar tracks, and sometimes we had to pause and laugh at the way we kept reflecting each other’s views. His terminal illlness never once intruded into our conversation, but its silent presence prompted us to speak all the more frankly and openly, and we exchanged some hilarious stories about our respective experiences as Westerners living among the Chinese, his in China, mine in Taiwan, each for eighteen years.

What I’d planned as a two-week visit stretched out to become a two-month sojourn. I would visit John three or four times a week, staying with him from early afternoon until sunset, then foray out into the sultry Bangkok night to do my field work on the city’s sensational night life. It was a heady blend-spiritually uplifting deliberations by day, sensually seductive pursuits by night, the dualistic poles of life on earth which cause such contradiction and anguish in Western civilization but which are smoothly integrated in Eastern life as complementary aspects of the human condition. This wise and compassionate compromise between the physical cravings and the spiritual yearnings which all humans feel, without the compulsive need to sacrifice one for the other, is one of the greatest gifts which traditional Chinese civilization has to offer the world. It’s a theme that appears often in John’s books, and it arose repeatedly in our conversations.

Sometimes John’s health would rally with a sudden surge of energy, and we’d go out for dinner with his family and friends. He always chose one of his favorite Chinese restaurants, where he knew the chefs and could go into the kitchen to tell them exactly how he wanted the food prepared. At the table, he and I kept up a running dialogue in Mandarin Chinese to which only we and the waiters were privy. His adopted Thai daughter Bom usually joined us for these culinary extravaganzas, as did Susan, his daughter by his Chinese wife, who was visiting from England. Somehow John always managed to arrange things so that almost all of the guests who joined us at these lavish Chinese banquets were both Asian and female, which allowed us to share another one of our favorite Chinese traditions, enjoying good food and wine in the company of charming women.

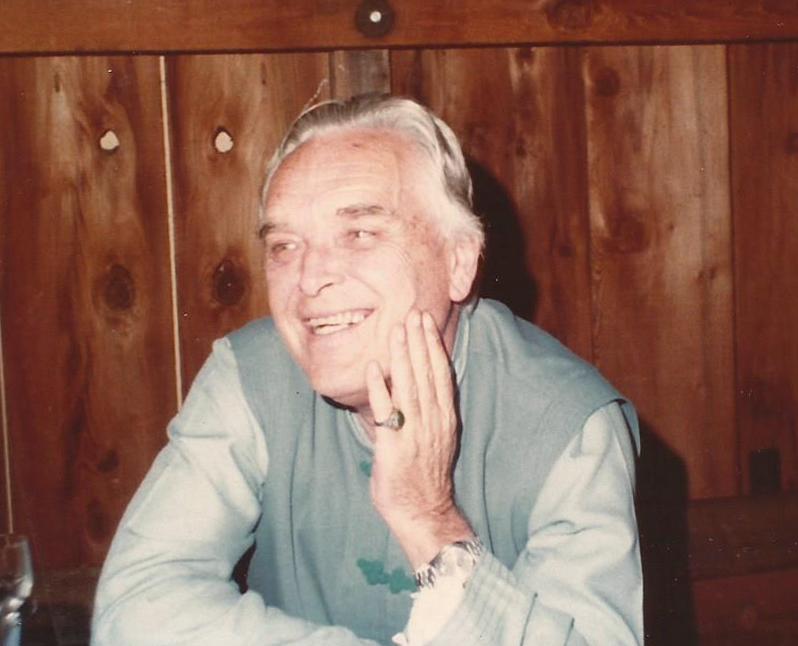

I got to know and like John well during those two months in Bangkok. In many ways, his life was a mirror that reflected key aspects of my own life, both past and future, and in me he found a friend who felt as enamoured and nostalgic about the vanished splendors of old China as he did. We were both what I call sinopaths. While a sinophile is simply a scholar with an intellectual interest in China, a sinopath has a visceral interest that runs far deeper than scholarship, pursuing an almost pathological obsession with all things Chinese and molding his life to the model. When I met John, he even looked Chinese, with his Fu Manchu moustache and goatee, his frog-buttoned Chinese chemise and baggy silk trousers, his straw sandals and old-fashioned Chinese mannerisms.

Finally, regrettably, it came time for me to leave. I’d spent my entire expense account and had two deadlines to meet the following week. On my last visit to the House of Wind and Cloud, John invited me to stay for dinner with him at home, just the two of us. He kept a special cook in his household whose sole job was to prepare authentic Chinese food for him, and that evening she outdid herself to impress John’s newfound friend. As we ate, we mused over some lines of Chinese poetry brushed in elegant calligraphy on a tattered old scroll hanging by the dining table. Plumbing our minds for just the right words and images, by the time dessert came we’d deciphered the poem and rendered it into fairly good English verse. He seemed overjoyed by this accomplishment, and felt greatly relieved as well.

“For years I’ve been pondering the meaning of those lines as I sat here alone having dinner,” he said, “but with so many possible interpretations and no one else to discuss it with, I never felt that I got them quite right. Now I have, thanks to your help, and I can tell you that it’s a load off my mind!”

We celebrated our achievment with a toast and drained a few more cups of the special Chinese wine he’d opened for dinner. The next morning I flew back home to Taipei. The only line I still remember from that poem is, The pines sigh in the breeze. Exactly one month later, in early June, I received a letter from his daughter Bom, informing me that John had died.

In July, en route back to Taipei from an assignment in Singapore, I stopped briefly in Bangkok and paid a visit to the House of Wind and Cloud. A somber pall hung over the house. Even the chimes were silent. “My father’s still here,” Bom whispered, nodding her head towards the shrineroom upstairs. “We haven’t been able to find a place to keep his ashes.”

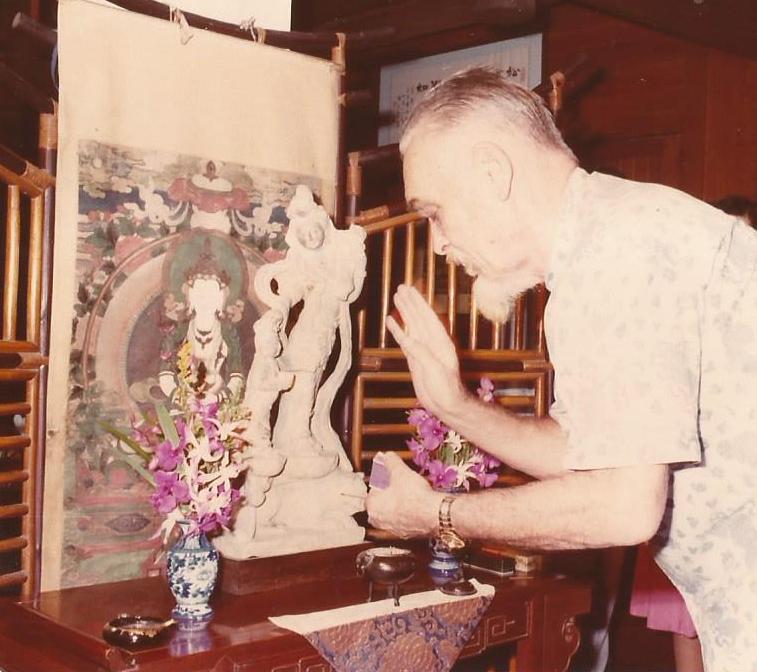

John’s last wish had been to have his ashes interred in a Kuan Yin temple in Thailand. Kuan Yin, the beloved Chinese Goddess of Mercy, had always been John’s favorite Buddhist deity, and he devoted an entire book to her, Bodhisattva of Compassion: The Mystical Tradition of Kuan Yin. After John’s cremation, Bom had gone to all the Kuan Yin temples in and around Bangkok, trying to find a final resting place for her father’s remains, in order to fulfill his wishes.To her great surprise and frustration, not a single Buddhist temple in Bangkok, where John had made his home for 35 years, would accept his ashes, even though he’d been a devoted Buddhist all of his life and his books had been instrumental in introducing Buddhism to the Western world. So his ashes remained in an urn in his shrineroom, unsettling the entire household of family and servants, who felt the restless presence of his lingering spirit. No one dared go upstairs except for Bom’s ten-year-old daughter June, who often went up to commune with her grandfather.“She goes up there all the time,” Bom said with an involuntary shudder, “and talks to him.” I went up to the shrineroom to pay my respects and returned to Taipei the next day.

Later that year, in December, I returned to Thailand on holiday, and the first place I went was the House of Wind and Cloud. Bom opened the gate beaming with a big smile. “We found his temple!” she exclaimed.

Later that year, in December, I returned to Thailand on holiday, and the first place I went was the House of Wind and Cloud. Bom opened the gate beaming with a big smile. “We found his temple!” she exclaimed.

“His temple?”

“Yes, my father’s Kuan Yin temple, his final resting place, just as he wished! We’re taking him there next week. The ceremony is set for the 27th, and you absolutely must come. I’m so glad you’re here!”

She invited me upstairs to the tea pavilion, and we prepared Chinese tea in the same old Chinese pot John had used during my visits with him. While the tea steeped, she started to explain what had happened. “A few months ago, I began having this vivid dream. It was always the same. I saw my father sitting in a temple surrounded by monks. He looked so happy there. I called out to him, and he waved at me. ‘Bring me here,’ he said, ‘this is where I wish to be.’ But I was so overwhelmed by my emotions that I burst into tears and woke up crying. This continued for several weeks.”

She paused to gauge my reaction, wondering whether I thought she was crazy. But I’ve always believed in the significance of dreams, and I was already hooked by her story, so I urged her to continue.

Well, after a few weeks of this, I finally managed to control myself and pay attention to the details in the dream. For example, I noticed that the monks there wore grey robes, as they do in Chinese temples, not the saffron robes worn by monks in Thai temples. I also remembered a big yellow wall in front of the temple and a huge bodhi tree outside the main gate. And there was also a river. I finally realized that my father was using this dream to communicate with me, and that he wanted me to bring his ashes to that particular temple. I spent nearly two months driving all over Bangkok looking for that temple, especially along the Chao Phya River, but I found no place that looked anything like the temple in my dream.

She paused to pour us some tea, then continued. “Finally I got an idea. My father used to conduct temple tours of Thailand for foreign visitors on behalf of the Siam Society, so I went there and told them my problem. They were very nice about it, and they remembered my father well. I spent day after day there, looking through all the books and journals in their library, searching for a temple that matched the one in my dream, and finally I found it. It was in a monastery located in Kanchanaburi province, about a two-hour drive from Bangkok, so the very next day I drove out there to look.”

I could hardly bear the suspense. “What happened?”

“The moment I saw the place, I recognized it as the one in my dream! It was facing the River Kwai and had a big bodhi tree out in front, and a high yellow wall. I ran inside and found the abbot and told him the whole story. When I mentioned my father’s name, he smiled sweetly and said, “Of course you may bring your father to rest here. John was my good friend.” A tingling current rippled up my spine when I heard those words, raising the hairs on the back of my neck, and I felt an uplifting surge of energy as I realized that John’s spirit had been patiently guiding his daughter to this remote monastery, where he wanted his ashes to be interred and where the abbot was an old friend of his.

“Well, the abbot took me into the main shrinehall of the temple,” Bom continued, “and sure enough there was a big statue of Kuan Yin sitting on the central altar. The abbot smiled sweetly again and pointed up to a faded old photograph hanging above the side entrance to the shrine hall. I couldn’t believe my eyes! It was my father! He was standing next to another Englishman behind a chair in which the abbot himself was sitting. They all looked so young! The abbot told me that the photo had been taken in 1951, only a year after my father arrived in Thailand and nine years before I was born.” Tears welled up in her eyes and rolled down her cheeks, and for a while we sat there in silence. A breeze jingled the chimes.

Then she sighed and finished her story.“The abbot told me that my father had helped raise the money needed to finish building that monastery shortly after he came to Thailand, and that the picture had been taken on the day the main temple was formally consecrated. None of us ever knew anything about this, and my father never mentioned it. Not only is it a Chinese Kuan Yin temple, it also has a close connection with Tibetan Buddhism, which is extremely rare here in Thailand. As you know, my father’s main Buddhist teachers were Tibetan lamas. Anyway, the abbot invited me to stay for lunch, and after that he checked his calendar and told me that December 27 is the most auspicious day for the ceremony, so that’s when we’re taking my father’s ashes there. I do hope you’ll come.”

“I wouldn’t miss it for all the tea in China!” I replied, thanking my lucky stars that my trip to Thailand coincided with this event.

Bom and Susan and their husbands and children picked me up at the crack of dawn that morning, and we drove out to the monastery for the ceremony, which was scheduled for 8:00 AM. As soon as we arrived there, I recognized the Chinese and Tibetan scripts painted on the pillars at the main entrance, the Chinese style robes worn by the monks, and the Chinese and Tibetan iconography on the altars. Although John had lived the last 35 years of his life in Thailand, where Theravada Buddhism prevails, he practiced the Mahayana Buddhism of China and Tibet taught by his Chinese and Tibetan teachers. Through the connection he’d established with this Chinese monastery in Thailand, he insured himself a final resting place in the spiritual embrace of Kuan Yin, his beloved Bodhisattva of Compassion and the guiding light of Mahayana Buddhism. We were now bringing John home to rest in a Chinese monastery that taught the Tibetan school of Buddhism he practiced, with a Kuan Yin temple which he helped found during his first year in Thailand. The wheel of life had come full circle for him.

The ceremony was enchanting. For over an hour we sat on the floor in the shrinehall, while a dozen monks chanted Tibetan mantra in deep, vibrant tones, the air redolent with the fragrance of sandlewood incense. Lost in reverie, my head rocked gently to the mesmerizing cadence of the chant. This is how John must have felt half a century earlier when he visited those remote mountain monasteries in China, and the spiritual inspiration he found there glowed like a candle in his books.

The abbot clearly demonstrated his deep respect and affection for John by arrangeing for John’s ashes to be interred in the corner slot of a sacred stupa located on the terrace behind the temple. This is a rare honor even for a resident senior monk, and even more so for a foreign layman living in Thailand. The crypt was sealed with a marble plaque inscribed in gold with John’s name and dates of birth and death. After making offerings of incense, fruit, and prayer, we all joined the monks for a big vegetarian banquet in the courtyard.

After lunch I went to Kuan Yin’s shrinehall and gazed up at the faded photograph above the door. Again I felt that tremor run up my spine. There stood John in a starched collar and white linen suit, tall and handsome, next to another Englishman, with the youthful abbot sitting in a chair before them, holding a rosary. With John’s last wish fulfilled and Bom’s dream finally come true, we got in the car and drove back to Bangkok in silence.

Two years later I decided to move to Thailand. Taiwan had become too modern too fast for my traditional Chinese tastes, and had lost its old-fashioned Chinese charm, just as postwar China had lost its appeal for John. And like him, I took refuge in Thailand. For the first two months I shared a spacious house and garden with an old friend in Bangkok, but then a Taiwanese developer came along and bought the property to make room for a condominium, so we had to move out. Hearing of my predicament, Bom came over to visit me and said, “Why don’t you come and live in my father’s house? You were the last friend he made in this life, and he liked you so much. I know that he’d be happy to have you living there.”

So my wish to live in a traditional Thai house just like John’s was fulfilled. Almost three years to the day after first arriving at the House of Wind and Cloud to meet John, I became its resident writer and sinopath-in-exile, writing and sleeping in the very same room in which I’d spent so many memorable afternoons with John. So turns the wheel of life.

Excerpted from My Journey in Mystic China by Daniel Reid. Photos of John Blofeld, courtesy of his daughter Sue Molle.

Book by and about John Blofeld.