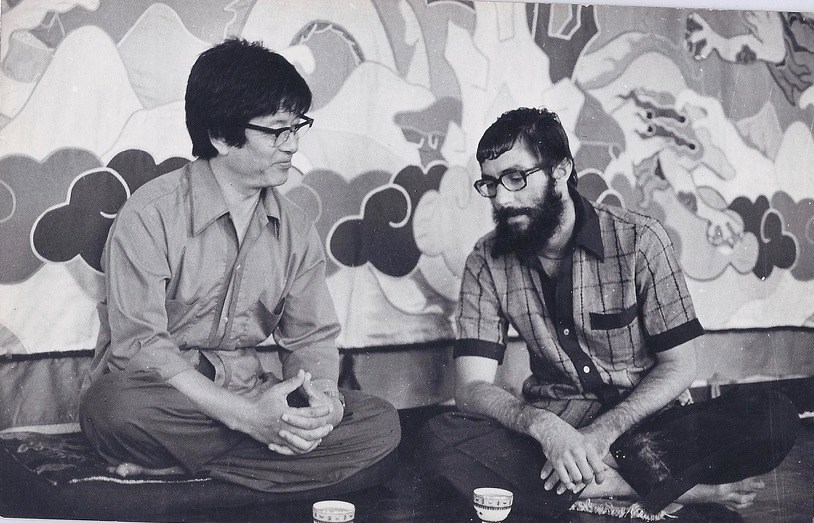

Interview with Dr. Emchi Shakya Dorje.

James Hinds: How do I really understand the mechanics – what’s happening in my body, what’s a simple way to explain your assessments and herbs that you gather or purchase, how can they help with everyday stress? How do they help with everyday mental stress, everyday dukkha ?

Shakya Dorje: With everyday stress, you should be looking more at handling the situation with your own mind and your own attitude rather than turning to any medication. But medicine is there to help; either for people who are not handling it or people who have such undue stress that it’s not even reasonable to expect them to handle it.

Body and mind are constantly interrelated. They are interrelating because the dynamics of body and mind are governed by three kinds of primal energies. These we call: wind, bile and phlegm. And on the one hand, the three primal energies are related to elements. So the bile is the element of heat, phlegm is the element of cold, wind is the element of movement. On the other hand, the three primal energies are also related to emotion. So, wind is related to desires and cravings and needs. Bile is related to anger, and thus also fear and defensiveness and so on. Phlegm is related to dullness; dullness is not normally something we think of as an emotion but it is. It’s an emotion we feel all the time, because we are constantly either ignoring or shutting things out, to focus on something else or to go to sleep. So, it is another emotion that is constantly functioning. So, as our body goes through various states both because of external circumstances, from nutrition, and so on, and also physical activity – our mind goes through various states. So these three kinds of dynamic energy are stimulated.

These three kinds of energy, I say types of energy because there are actually many of them in the organism carrying out different sorts of functions. But, according to how they are influenced, so they will change their patterns. If these three energies remain in balance they will function through the passages that they normally function through, and the organism will remain in health. If something happens to cause them to become unbalanced, usually it’s not one thing, but a nexus of different influences. Occasionally it’s one thing but the larger percentage of the case it’s a group of things, then, this will start to cause some sort of imbalance which can lead to illness.

In the case of stress, the biggest and most common influence of stress is to augment the wind element. The wind element is the element of movement; it governs both the physical movements and the autonomic movements of the organism. Things like the beating of the heart, the movement of the nervous system are governed by the wind element. So, the person comes under stress of different kinds, whether it’s by over work or emotional disappointment; emotional disappointment is usually related to something the person wants, hence, it disturbs the wind element. The wind element starts to dysfunction and the person, if the wind moves in certain ways it may cause something physical like an irregular heartbeat; it may cause something that is halfway between physical and emotional, like insomnia, or it may cause something completely emotional or mental, such as an inability to concentrate, disturbed thought pattern, and so on.

If it’s very bad, the person will start to have delusions. The reason for the specifics of this has to do with the passages of the body. Once the wind element gets disturbed, a little bit of disturbance will just affect its regular passages, but if it gets too disturbed, it will pass through other passages and some sorts of dysfunctions, or serious dysfunctions will happen. So, then the emchi looking at the case determines that the wind element has been disturbed, and one finds that not only was the person under stress but maybe they didn’t eat or couldn’t sleep or are overworked or exhausted or whatever. Secondary reasons, things which compounded the wind element.

So, the emchi will give some sort of instruction about diet. For the wind element, the person will be given a solid diet, usually a fairly solid diet and to eat regularly. Various lifestyle recommendations will be given, but then the herbal compounds are there first to bring the wind element to its regular level and secondly to get it to function in the passages it is meant to function through – not in some irregular fashion. This is one example. Not all stress actually is the wind element. I picked that because it’s the more common case.

James Hinds: Like, for example, anxiety – would that be a manifestation of disturbed wind?

Shakya Dorje: Anxiety. Yes, anxiety has to do with a complex of hope and fear and so this usually disturbs the wind element – even a fear being a projection of the future, it still tends to disturb the wind element and the problem one runs into, is when the wind element becomes disturbed, one naturally tends to feel more anxious. So the person starts out feeling anxious, it disturbs the wind element and makes them more anxious, the anxiety gets completely out of control. So a kind of an anxiety syndrome occurs; it is worth noting that in Tibetan medicine, it is important for the patient to take some responsibility for the cure.

We are not trying… besides from the fact that there are dietary things, lifestyle things that the person must implement – they have to take responsibility to implement them. They have to take their herbs, but also in having a commitment to be curative of the problem, trying to adapt ways in which can help, that’s important. As with most cases, the patient must take responsibility; at least with most cases I work with, that is quite important. So, if we talk about stress and anxiety; they are quite common things. Using mental illness as an umbrella, this is very common language from a clinical point of view and from Buddhist point of view. So, for things like schizophrenia, bipolar, spit personality disorder, a whole plethora of terms for diagnosis.

James Hinds: how does Tibetan medicine approach severe mental health disorders like sociopathy or narcissistic disorder? Is there any, ’cause obviously the go-to for Western society is medication.

Shakya Dorje: In terms of Tibetan medicine, these are more severe cases and they are going to need medical treatment. In some of the cases you mentioned, such as schizophrenia, for instance, and some others, these are kinds of disturbances of the heart wind, and in the finer passages of the heart. That is, for example, in the heart chakra that you’ve seen in Tibetan medicine. There are specific medicines to try to help the heart wind to function normally again. There is a second complex which has to do with the fire element, with bile…

James Hinds: and it is associated with anger?

Shakya Dorje: That’s right. Part of this can be characterial in that the person may have responded to certain circumstances in a way that was more particular to them. The fire element enters certain fine passages of the heart and this can lead to psychotic behavior or certain kinds of delusional behavior.

Other kinds of delusional behavior are from the wind element. But when you have a patient with heart heat, they are very convinced of their point of view and they have one point of view – their mind doesn’t jump around, and they speak and explain their point of view very rationally, despite the fact that this point of view may be completely irrational. To them it seems perfectly and clearly very rational, as you get with people with sociopathy etc. Sometimes this is heart heat, and if it is treated, it can get good results – if you recognize the symptoms. I don’t want to put a bad name on heart heat, because there are people who suffer from a minor level of this, where they are not by any means psychotic or sociopathic.

Shakya Dorje: But they do have a little bit of this. I don’t want to give them a bad name, but in extreme cases, it can get bad because it’s another sort of syndrome which one gets with psychological results.

James Hinds: Would you say, okay just to jump topics a little bit, would you say that Tibetan medicine, as a system of well-being, can circumvent karma? Because someone’s karma is someone’s karma, right? If you get cancer, for example. Can Tibetan medicine change karma? I guess it comes down to a person’s own responsibility. Because I know we were talking about our dharma brother recently and his condition and it’s like he just has to go through it; he just has to go through the whole process and he’s doing better, but at the time it seemed like his illness would be forever, and nothing seemed to work, you know.

Shakya Dorje: There are different kinds of illness and in the case where the karma of the illness is so dominant that medicinal treatment of any kind doesn’t work. But a large number of illnesses are not karmic to that extent. After all, what karma comes to fruition is dependent upon circumstance. You change the circumstances; you change something. So if the illness presents itself in such a way that it is no longer dependent upon any circumstances, then that is a problem. But very often the illness is still dependent on circumstances.

So by changing the circumstance, you can still do something. That means therefore that the karma of that illness was not such that under all circumstances it would continue. Karma is very complex. So, this is why in many cases, even if a person has an illness, there can be something to be done about it. But most illnesses, aside from things which are completely integrated with the body – such as congenital illnesses, congenital conditions, that is to say, aside from those, most everything ought to be treatable. Occasionally one sees something that even if in theory it is treatable, does not respond; you can see that the person’s karma for this illness is quite strong.

James Hinds: How would you compare medication and the suggestions of a western medical doctor to the suggestions and medications of an emchi? For example, herbs for wind imbalance versus medication such as an antidepressant.

Shakya Dorje: I think the best way to answer that question is to point out that I’m not the kind of person who’s opposed to Western medicine. Western medicine has a lot of positive things to offer. But the thing is, the way you think in Tibetan medicine and the way you think in Western medicine is sort of opposite. So, in Western medicine, the logic is reductive. They try to find either a particular agent which is causing the illness, or a particular substance in the body, because Western medicine is materialist – what is causing the problem and to treat that. And that approach can have some benefits.

In Tibetan medicine, we go in the other direction. We try to find out about the details of the illness, not just by talking to the patient, but by taking the pulse and a urine sample in order to build a global picture of the whole organism. Then, we try to treat the whole organism, trying to bring the whole organism into some kind of balance. When you have treatment, you will have results against a specific illness, specific problems. So in Western medicine, they are trying to reduce down to find one little cause. In Tibetan medicine, we are trying to build up to find a global picture.

Any kind of this discussion tends to get oversimplified, because in some cases, especially in acute illness, you have to look for a specific cause and treat that. In Tibetan medicine, you look for something we think of as the essence of the illness. From our point of view, Western medicine is looking for a symptom. They may think they’re looking for a cause – from their point of view they are looking for a cause, but from our point of view they are looking for a symptom and treating a symptom. We are looking for the essence of an illness and trying to treat that.

James Hinds: So a symptom could be red herring, so to speak? It could be a distraction from what is happening with the patient.

Shakya Dorje: That is an interesting question, because my teacher Trogawa Rinpoche used to say: “all the evidence should lead you to one conclusion.” Everything should point to one complex which you understand. But another one of my teachers, Tenzin Chodrak used to say, never trust symptoms. First of all, people don’t know what’s important; they are just people with symptoms, in a medical sense they don’t know what is important. They may tell you something that is relatively irrelevant and leave out something that is really important. So you can’t really trust symptoms. That is why Tenzin Chodrak had a great capacity with the pulse. He was basing it on… he trusted the technical diagnosis of the pulse and the urine and he had come to lean heavily on those to reach his conclusions. I studied with both masters.

James Hinds: So you kind of see both approaches as correct?

Shakya Dorje: Yes. As you judge with the individual the information they give you, and sometimes they understand the situation alright and sometimes they don’t.

James Hinds: Right, well it’s the same for me in the field, as a paramedic. I look for symptoms because I’m treating the immediate; the symptoms are my gold. That’s what I want to know, what are your symptoms? They might not know that an irregular heartbeat could be dangerous, so they might not mention it.

When I go into a scene, I want my spatial awareness sharp – are there other people? are there weapons around? how is this person in distress? And I kind of have to do it really quickly to figure out if I need to stay or leave or what I need to do. But you have a little more time in your clinic, so what do you look for when a person walks in? When a patient walks in and you meet them for the first time, what do you look for in their demeanor, in their facial expressions and body language that could contribute to your assessment?

Shakya Dorje: When the patient enters the room, already you can tell something about their elemental balance, where they are at. There are a lot of signs. A person who has, just an example, a person who has a wind imbalance; wind is the element of movement, so its imbalance leads to irregularity, so the person will shuffle and will be hesitant and they have a particular stance which we call the vulture position. It rather looks like a vulture, like a curve in their upper back, this is not a curve due to a spinal problem, it is a feeling position they put themselves in, even though they could stand up straight.

And they may tremble, breath irregularly, and if you have a heat source in the room, instead of sitting where they are supposed to, they will go over and stand or sit by the heat source, because people with wind imbalance constantly feel cold, they become very sensitive, so they can’t stand discomfort, so feeling a bit cold is a problem for them.

People with bile problems will be standing up straight and march in and they will tell you what they think their problem is. And you must be careful with people with bile problems; bile is related to aggression, and they also do not, in many cases, people with bile problems do not take well to being told something other than what they think. They are stuck on their own opinion. However, most especially if principle or functional organs are affected, they become debilitated and become more susceptible. People with phlegm problems move slowly and they amble and they breath heavily and they may be swaybacked and once they have sat down it is difficult for them to get up, not because of their joints, but because phlegm is heavy and slow and it makes them feel very heavy, and so once they sit down, it’s a lot of work for them to get up.

When you talk to a person with a phlegm problem, well talking to them is not very useful, because they don’t know what their problem is and if they did know it at one time, they forgot. You have to figure it out by yourself because they are not very communicative, because phlegm slows things down and their intellectual processes get slowed down. So just from the demeanour of the person, you can tell something about them right away. But I think whether they learn it or not, every physician in every system learns to look at a patient and tell something about them.

James Hinds: Which is not unique to medicine. You walk into a therapist’s room and they’re going to be looking for the same things, I suppose.

Shakya Dorje: For instance, once you’ve seen tuberculosis a number of times, someone walks into the room with tuberculosis, you can see it on them right away, and you can almost tell which stage they are at.

Shakya Dorje: Once you have some experience, you get pretty… some illnesses show strong marks.

James Hinds: That leads to another question about beings without bodies that could be associated with illness; spirits, so to speak. What is the general idea – is there a way to diagnose if someone is being followed?

Shakya Dorje: A spirit.

James Hinds: Yes, some affliction, causing illness. We’ve all heard those stories about –

Shakya Dorje: This is first of all not seen as such a common occurrence. However, in traditional Tibetan thought, people see the world as being alive and filled with spirits or spirit energies; all different cultures may see things differently, but Tibetans will see mountains as the palace of the mountains, forests as the home of the forest spirits and so on. It was only modern man who became materialist and stopped seeing the world in this way and so began to inhabit a dead world. Modern man inhabits a dead world where traditional people inhabit a living world. They see the world around them as alive, which is why all traditional peoples have a good, healthy respect for the environment. Where modern man went wrong is a question of vision. He sees it as an object, and once you see the world as an object, that is an aggression mode and you are fully justified in destroying it. In traditional Tibetan thought, if you cut down old trees or plough new ground or disturb boulders or if you procure the land where such has happened, then you may disturb the spirits associated with that, and then this can cause an illness. So Tibetans might commonly deal with this ritually, but I would like to tell you a story:

It’s a true story and it concerns my medicine master, Trogawa Rinpoche. We were in the United States and he was approached by a man in his late 30’s who had cancer. The Western treatment had failed, and so he had been given only a few months to live. Rinpoche took his pulse and he paused because he didn’t know if the man would accept what he had to say or not.

Then he said, “This has to do with disturbing a spirit. It is a water spirit and the spirit is white and it is a stone which belonged to the spirit which was disturbed; that’s why you have this illness.”

And the man said, “I’m a gem trader. I have a warehouse full of stones. How am I going to figure this out? How would I ever figure this out?” Rinpoche said, “Go to your warehouse and look for the white stone and just look through them; you’re going to find the stone, it’s going to be a stone that feels completely different from all the others”.

The man went away and he didn’t really believe what Rinpoche had said. He went back to his warehouse and started looking through his stones and he found a white stone; he said this stone gave him a totally different feeling than anything else he had been working with in the field of stones and previous gems, and so he took this and it was a stone that he had gotten in a trade, not one that he had mined himself. Rinpoche then told him to go east and return it to the water. So he did that, he returned it to a spring. Then Rinpoche gave him some treatment, and after that the treatment worked; this man is alive today. That happened in 1984, that’s 32 years now. And he had 3 months at the time. I wouldn’t want to say that happens all the time. On the other hand, a traditional Tibetan would say that the wholesale destruction of the environment has caused the outbreak of great modern illness such as cancer; that would be a common response.

James Hinds: I see. So, how much of Tibetan lore and mythology is a part of Tibetan medicine as a medical system? Is there some places in your studies where you kind of had to say to yourself, ‘is this Tibetan mythology or is this pure medicine’?

Shakya Dorje: I would say not too much. There is actually one section, three chapters, in the classics where spirits are discussed. And so we learned about these. But they don’t come too much into practice. On the other hand, a lot of lore in Tibetan medicine about the properties of plants and the properties of minerals and how they are used, that has to do with ancient lore; that kind of lore is being used constantly.

Interviewed by James Hinds on the evening of July 25, 2016 in Shakya’s Medical Office and Home. Transcribed by Gerry Thorpe and James Hinds.

Emchi Shakya Dorje’s website.

Featured image by Engin Akyurt, Cambodia.