I confess to not being open to the present moment and the potential therein.

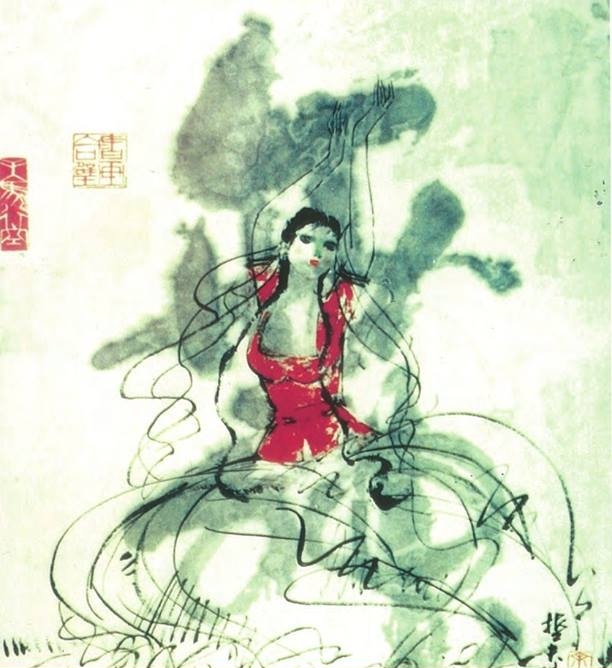

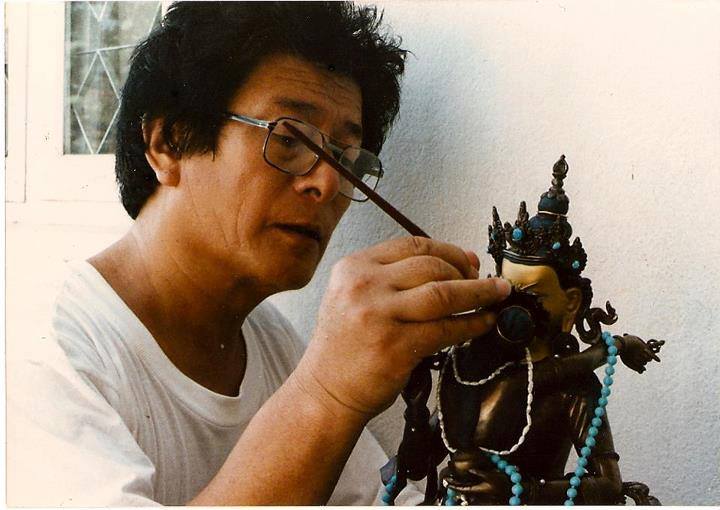

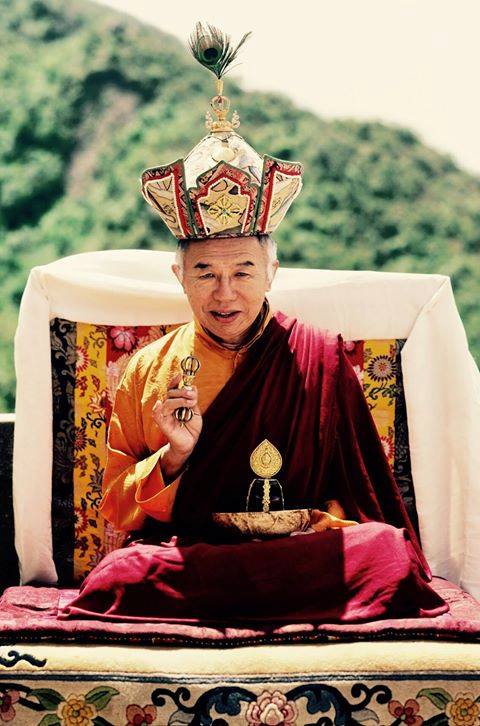

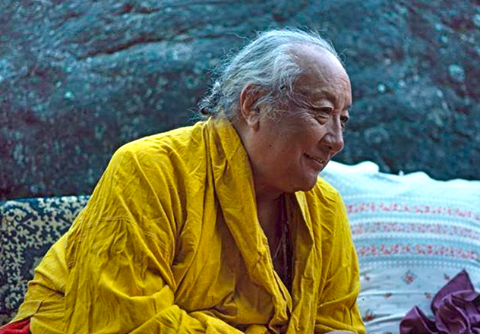

All of the realized masters that I have had the good fortune to encounter have exhibited certain undeniable characteristics in common—humility, regal dignity, sharpness of intellect, overflowing compassion and love, unwavering faith in the Three Jewels and the infallibility of karma, as well as incomparable appreciation for their teachers and the teachings. These qualities are not mind-blowing, astounding, miracle-producing spectacles, but are the core of what accomplishment is about. Being in the presence of such amazing individuals is like basking in the warmth of sunshine on a freezing day and is no different than being magnetized by the sparkling, heartrending sincerity displayed by enlightenment. They are representations of the physical embodiment of purity, effortless mindfulness, and carefulness. They exhibit diligence in fully intermingling life and practice, selflessly fulfilling the benefit of beings. As Thinley Norbu Rinpoche explains, “Even if we use ordinary intellectual power, when we meet with people who use pure noble intelligent power, we automatically get a sense of expansiveness rather than one of rejection or confinement to a lower level. In this way, some pure and gifted meditators create a field of bliss around themselves through their spontaneous luminous power, and use their pure elements to help others attain the same level and join with them in the same mandala and same mind.”

The energy, openness, and empathy of these masters are the results of having overcome ignorance and any speck of ego clinging, self-protection, and aggression. These qualities accommodate a fearlessness that can deal with all situations without being threatened or humiliated. An example of this is given by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche: “Many Buddhist teachers were abused, treated as criminals, and beaten when the Chinese communists came to Tibet. Instead of feeling hatred, they prayed that the negative actions of all beings would be purified through the vindictive attacks against them.”

Once ignorance has been purified and self-clinging vanquished, the possibilities are limitless like space. This vastness is the reality of a realized yogi. We, conversely, are limited like the space held firmly in the grip of our hands, as we clench our fists in desperation, trying to establish our worth and validity in unaware, erroneous terms. Let’s review this road map that leads to the exalted state of a realized yogi where everything is possible and attainable.

Earlier in the book, ground was defined as the basis of all, the original purity. Enlightened beings have never strayed from this state of primordial purity, whereas sentient beings became separated from it by “not recognizing their own naturally occurring self-manifestation of the great empty original purity.” This marks the delineation between buddhas and beings: buddhas are undeluded, while beings have fallen under the power of confusion. To become re-enlightened, we must undergo the path of trainings that purify the obscurations we have collected as a result of nonrecognition. Yogis take hold of the path and endeavor to cleanse the temporary stains. Once these stains are purified and the accumulations perfected, realized yogis attain the result or the fruition by being reestablished in the innate pure nature.

Because we misconstrued pure phenomena, it solidified into gross commonly accepted phenomena and sentient beings split away from the natural state. Everything was divided up into subject and object. Dualistic mind increasingly fortifies its deluded habits and strays further and further away from the basic ground of awareness wisdom. So, our original body, speech, and mind that were no different from the enlightened body, speech, and mind of all the buddhas have become increasingly coarse and rough and are what we experience now as the body of flesh and blood, fragmented speech, and bewildered mind. We can return to our pure state because it is the source from which we strayed. In fact, all relative things originate from the ultimate. If this were not the case, we could never become re-enlightened, just as it is impossible to turn sand into a diamond.

We can easily understand how our experience is different from that of the Buddha, but how do we differ from an accomplished yogi traversing the path? The various Dzogchen instruction manuals explain that thoughts occur in the same way for ordinary people and yogis; however, whereas ordinary people are carried away by thoughts, a yogi is trained in the key instruction of liberation of thought at the time of arising. The common analogy is that a yogi’s thoughts are like drawings on water, disappearing the moment they are formed. For the rest of us, thoughts are like drawings in stone—they are carved deeply and imprinted. This is how we encounter reality. We live with our minds, so this is not foreign to us. Thoughts are being created morning until evening, and rerun endlessly with a strong tendency to be taken as true and concrete. We reinforce thoughts by a continual repetition of our point of view, over and over and over again. Even when we are not under the influence of coarse thoughts, we walk around with a subtle narrator who constantly refers back to ourselves and incessantly evaluates that which is seemingly beneficial or harmful to us.

Initiating intellectual investigation and effort to dismantle the solidity of self, thoughts, and perceptions helps to lighten this tight grip of grasping, as all spiritual practices do. But to totally destroy delusion from the root and to become reestablished in the exalted state of enlightenment in this very body and life-time, rigpa needs to be introduced, recognized, and trained in until this innate self-originating awareness is stabilized. Realized yogis have done this, and that is the primary reason why they experience phenomena so differently than we do. As Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche has taught,

The simple definition of mind is the unity of being emptiness and cognizance; it is complete within that sentence. Its essence is empty; its nature is cognizant; its capacity is that these two cannot be taken apart. That is the meaning of unity— impossible to separate; emptiness and cognizance cannot be divided. That is the state of affairs in all beings, yet they do not experience it.

As is stated in the Mahaprajnaparamita, “Transcendental knowledge (prajnaparamita), which is inexpressible, inconceivable, and indescribable, nonarising and nonceasing, is the essence of space itself.” It is the experience of individual cognizance, self-cognizant wakefulness or wisdom. In the case of sentient beings, it is the experience of an individual ignorance, but for yogis it is the unity of emptiness and cognizance suffused with awareness; for sentient beings it is emptiness and cognizance suffused with ignorance.

As we know, our way of operating is through subject-object fixation and grasping, always reinforcing the ego’s impressions. A yogi is aware of all that transpires, but does not obsess upon it, follow after objects of perception, or get carried away by discursive thinking. Yogis are not zombies: their senses are wide open and alert, but the incessant inner dialogue has ceased, and thought movement, which is freed upon arising, does not control them. Khenpo Tsultrim Gyatso explains a yogi’s perception as follows:

Mind is the mode of cognition that is involved with a distinctly apprehended subject, awareness the mode of cognition that transcends such a split. Mind is conceptual; awareness transcends conceptual cognition. From the ultimate point of view, mind is considered an obscuration, awareness a self-arisen wisdom that is aware of itself. For such wisdom, what is aware is in no way distinct from what it is aware of. It is cognition that has the capacity to directly and fully recognize and rest in its own nature. The awareness of the lack of self-nature is called yogic direct valid cognition; it is aware of the nature of things, the emptiness of the apprehended and the apprehending.

Mingyur Rinpoche concludes through science as well as meditation that:

Clinical studies indicate that the practice of meditation extends the mechanism of neuronal synchrony to a point where the perceiver can begin to recognize consciously that his or her mind and the experiences or objects that his or her mind perceives are one and the same. In other words, the practice of meditation over a long period dissolves artificial distinctions between subject and object—which in turn offers the perceiver the freedom to determine the quality of his or her own experience, the freedom to distinguish between what is real and what is merely an appearance.

Dissolving the distinction between subject and object, however, doesn’t mean that perception becomes a great big blur. You still continue to perceive experience in terms of subject and object, while at the same time recognizing that the distinction is essentially conceptual. In other words, the perception of an object is not different from the mind that perceives it. . . .

In the same way, in waking life, transcending the distinction between subject and object is equivalent to recognizing that whatever you experience is not separate from the mind that experiences it. Waking life doesn’t stop, but your experience or perception of it shifts from one of limitation to one of wonder and amazement.

How do we arrive at the same level that realized yogis who have taken hold of the undeluded wisdom aspect of their minds achieve, and maintain that in all situations of meditation practice and daily life? We practitioners on the path need to do the same, and reconnect with our essential nature and train in it. We need to make sincere supplications to our teachers to have the merit to receive the blessings to meet buddha nature and then apply that correct recognition diligently in practice so that “dualistic habit is reduced and nondualistic wisdom phenomena expands.” The more we train in sustaining the continuity of wisdom awareness, the less our grasping and fixating mind will control us, and we draw closer to a yogi’s pure experience, which is open and free. As Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche describes, for a yogi, rigpa becomes easy to recognize and maintain. “Yogi means having some degree of stability in the recognition of rigpa. For such a practitioner, everything looks different. Reality is different from how ordinary people believe it to be and experience it. Padmasambhava and Milarepa were not obstructed by what we believe to be solid matter. The seeming solidity of their own bodies and the seeming solidity of matter were totally interpenetrable. They could walk on water and were unharmed by fire.”

Those of us who have committed to this path have the incredibly great fortune to have encountered the precious teachings of the Buddha as well as living teachers who offer us the opportunity to study those teachings and assist us in training in them. Such a situation is a source of rejoicing that fills my heart with gratitude. It doesn’t matter that the path is long and difficult; it is the journey itself that is important. We must keep mindfulness as a constant guide and stay determined not to give up until reaching the exalted state. What a destination it is: to arrive at the state of a realized yogi and eventually buddhahood, where there are no opponents, no strivings, where we can act for the benefit of others without premeditation, since we have nothing to hold on to, cherish, or protect. We have put so much effort into propping up the unreal and reinforcing such a pointless pursuit. How sad and ironic—now we can rise above that.

These days, we also have the fortunate situation of technology that works to our advantage for the study of the Dharma. There are incredible supports in media, audio and video files, Web sites bursting with information, and of course books and transcripts. Many dedicated translators have produced practice materials, commentaries, and sadhanas for us in our native languages. It is impressive and inspiring. All these opportunities to learn, review, and contemplate are essential. Thanks to podcasts and webcasts, we are never far from our teachers and their teachings, though they are on the other side of the world.

However, there is no substitute for direct contact and an ongoing relationship with a living teacher. So it is critical to find the right teacher and create the time to ask questions to clarify any doubts. Any opportunity should be seized with him or her to discuss practice and any obstacles that may have arisen. One should not waste time with the teacher talking about mundane situations, such as office or domestic problems, especially if one has had the great merit to be introduced to the nature of mind and actually recognize it. One should not leave it with that one time, but continually train, as much as possible, in meditation sessions and daily-life experiences. As Lerab Lingpa advises, “Rely on authentic holy lamas who are learned and accomplished and whose motivation is altruistic. For the rest of your life, do not waver from seeking out such masters and hearing teachings directly from them.”

To paraphrase an insightful statement by Suzuki Roshi, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, in the expert’s mind very few.” Every moment that we are alive is a fresh opportunity for renewal, change, and rebirth. We continually have the chance to break away from standardized patterns, but we don’t seize the opening. Instead we fall into the comfort of habit that undermines the possibility of our liberation. Such dualistic patterns ruin us, moment after moment, day after day, life after life, shackling us to samsara’s prison, from which we could break out if we simply demolished the chains of grasping to solidity and awakened to our innate nature. Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche says, “To be a true yogi is to connect with that which is naturally so, bringing the natural state into actual experience. Once you have recognized the natural state—in other words, once it is an actuality in your living experience—people can truly say, ‘The yogi has arrived,’ when you walk into a room! Your body is still that of a human being, but your mind is free.”

Tulku Thondup Rinpoche tells the story of a great yogi named Chatralwa (literally, “the renunciate”) who was visited one day by a lama who could not reconcile the hermit’s comfortable life with his name. Sensing the lama’s discomfort, the yogi asked him what the matter was. The lama responded, “I heard that you are a hermit, but in fact, you have collected enough to be called a rich man.” Chatralwa replied, “A renunciate is someone who has gotten rid of his or her emotional attachments to worldly goods or to life itself. It does not mean being poor and hankering for them as many do.”

We strayed progressively from the primordial state to arrive at where we are at present, but we have the opportunity to regain control of our destinies, reverse this downward spiral, and return to our true nature. All the practices, aspirations, and teachings are conduits for the key point of the view, which once recognized and trained in, we can actualize in practice and daily life. Eventually as stability in the natural state is established, everything becomes the expression of rigpa. Bring to mind the teaching that Tilopa gave to Naropa: “Experiences do not harm you, clinging to them does. So cut your clinging, Naropa.” Once we have established the natural state, then we can say yes to possibilities, because all experience is a sublime cause for the accumulation of merit. When ignorance is purified, ego fixation has ceased, and subject and object are gone, all phenomena are experienced as the pure display of awareness wisdom.

The quotations are from:

- Thinley Norbu, Magic Dance, 77.

- Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, The Heart Treasure of Compassion, 124.

- Thinley Norbu, A Cascading Waterfall of Nectar, 21.

- Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche (unpublished teaching, 1985).

- Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche (unpublished teaching, 1985).

- Khenpo Tsultrim Gyatso, The Practice of Spontaneous Presence.

- Mingyur Rinpoche, Joy of Living, 82.

- Thinley Norbu, Welcoming Flowers: From Across the Threshold of Hope. 42.

- Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, Vajra Speech, 210.

- Lerab Lingpa, The Profound Drop of Vimala According to the Great Chetsun, 170.

- Tulku Thondup, Masters of Meditation and Miracles, 263.