This year, I find myself away from home on Christmas Eve for the first time. It’s not as if I’ll be missing out on much. Things will play out as they always have. In the morning, my dad and three sisters will walk our new puppy to go get coffee. Last year, we walked our other dog, Charger, but he died in April. Years before that we walked Blazer, but he died when I was fourteen. By the time they get back from the walk, my grandmother will have arrived. She’ll be drinking black coffee, no sugar, at the dining table with my mom. After an hour or so of visiting, my mother and grandmother will drive off to go antique shopping while my dad and sisters frantically scurry about wrapping last minute presents. The six of them will have Italian food at the fancy Trattoria down the street around 6, my dad will foot the hefty bill, and everyone will drive home for ice cream and a movie.

When I came home for Christmas last year, I was left with the impression that it wasn’t something I needed to do anymore. As I watched each of my family members slip into their designated roles, I internally groaned, sighed and mourned the repetitive banality inhabited by the upper middle class American family. Was anyone even enjoying this?

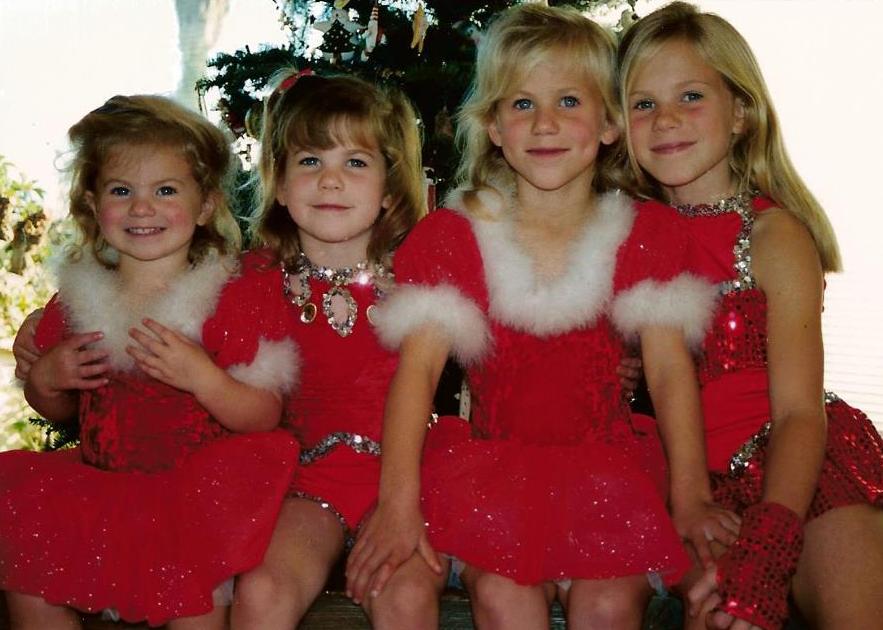

The weeks leading up to Christmas were worse. The Christmas photo posing, the attempts to spin the lives of four rather wayward offspring into something digestible for Christmas letters, the piles of presents that lose their magic as soon as they’re unwrapped. The aggressive SUV moms who cut you off in the congested parking lots of one of San Diego’s hundreds of bougie shopping centers. You know, the kind that have neatly trimmed palm trees sugarcoated with blinking fairy lights, red ribbons and fake snow for the holidays. The heinous amounts of electricity wasted on suburban Christmas light competitions. The stress of having to see your entire family. The dread of having to see friends from home. The Christmas songs that we’ve all heard every year of our lives since forever, but for some reason everyone still seems excited about them. The nation-wide permissibility of insulting kids’ intelligence by convincing them that an old man comes through the chimney and leaves a pile of presents, as if Christmas is a day when material commodities (made in China, India and Indonesia) come free of charge and social consequences. The advertisements, the spending, the nagging suspicion that what we’re really celebrating is the sovereignty of Target, JC Penny, Khols and Sur le Table over the Porsche driving masses. Don’t even get me started about pig genocide and honey baked hams.

So here I am in Kathmandu on Christmas Eve, on the other side of the world from my family, safe from the ravages of the holidays in upper middle class, white America. Yet here I am, having escaped Christmas, yet the only thing I seem to be able to write about is Christmas.

So far, it hasn’t been a very spectacular day. I woke up sick but had run out of tissues, so I spent that sleepy hour between dreaming and waking using my last clean sock as a snot rag. I looked at the pile of work at the foot of my bed and reluctantly pulled it towards me. I went through the motions of making and eating breakfast, trying not to be mindful of the fact that I was alone in an apartment in Nepal while my family was together in our house in California.

From this distance, I see that the annual performance of Christmas at home is a kindness we give to one another. As our lives careen towards uncertain futures in an increasingly volatile world, Christmas gives us the opportunity to willfully pretend that things aren’t changing. We’re not getting older. We’re not having quarter- or mid- life crises. My sisters and I can still come home and be eight, ten, twelve and fourteen. Charger’s and Blazer’s stockings still hang from the mantle next to the puppy’s, and Santa fills them with dog treats every Christmas Eve as if they haven’t died. We extend to one another the comfort of pretend permanence.

Every year, my mom gets upset that we sat around joking, reading and messing around with Charger or Blazer or the new puppy instead of helping her mash the potatoes for family dinner Christmas night. My dad and her wind up fighting because he didn’t do anything to stop the messing around. In fact, he participated. Madeline, the youngest, will feel stressed from the fighting. Barbara, who’s two years older than me, will try to get everyone together again. Whitney, the oldest, will have left dramatically to go to a yoga class or go surfing instead of spending time with us, like she’s supposed to. I’ll have slipped into my own world, binge reading whatever novels I unwrapped this year. Grandma will sit there sipping her coffee and acting like everything’s fine. Our innocent dysfunction is so comforting. The frustrations we have with one another never seem to change.

Outside of the illusory holiday bubble, the climate’s changing, wars rage in the Middle East and Africa, an angry toddler in the body of an incompetent businessman is the president elect of the United States, and my tiny life as a struggling twenty-something writer in Kathmandu tilts closer and closer to failure and disappointment. But, had I come home for December, the well-dressed woman who would have flipped me off while driving a Lexus in a crowded parking lot would be reliable as ever.

Photo by author.